ESSAY // lettrism + the failure of aesthetic action

“We had to demolish Charlie Chaplin, but it was a directly political issue.”

This week, returning to my favorite thing to write about, namely avant-gardists whining and fighting with each other. To that end: another big essay zooming in on another endlessly recursive tendril of countercultural history, this time the split in the Lettrist movement--the postwar Parisian avant-garde set whose leadership squabbles pitted the group’s founder, Isidore Isou, against the upstart Guy Debord.

On one level, this text is an account of schoolboy bullying among the members of a tiny and marginal social scene (emphasis on boy; the struggle between Isou and Debord could be summarized as a dispute over which macho clown did a better job publicly humiliating his better-loved forebear); but the schism also had real effects on the development of the international avant-garde. If Debord’s later development of the Situationist International and its long-debated impacts on political history constitutes the better-known story here, it’s the Lettrism split that lays the groundwork.

It’s also, according to me, an unaccountably fun story. But what do I know??

And their revolts became conformisms,

Mark

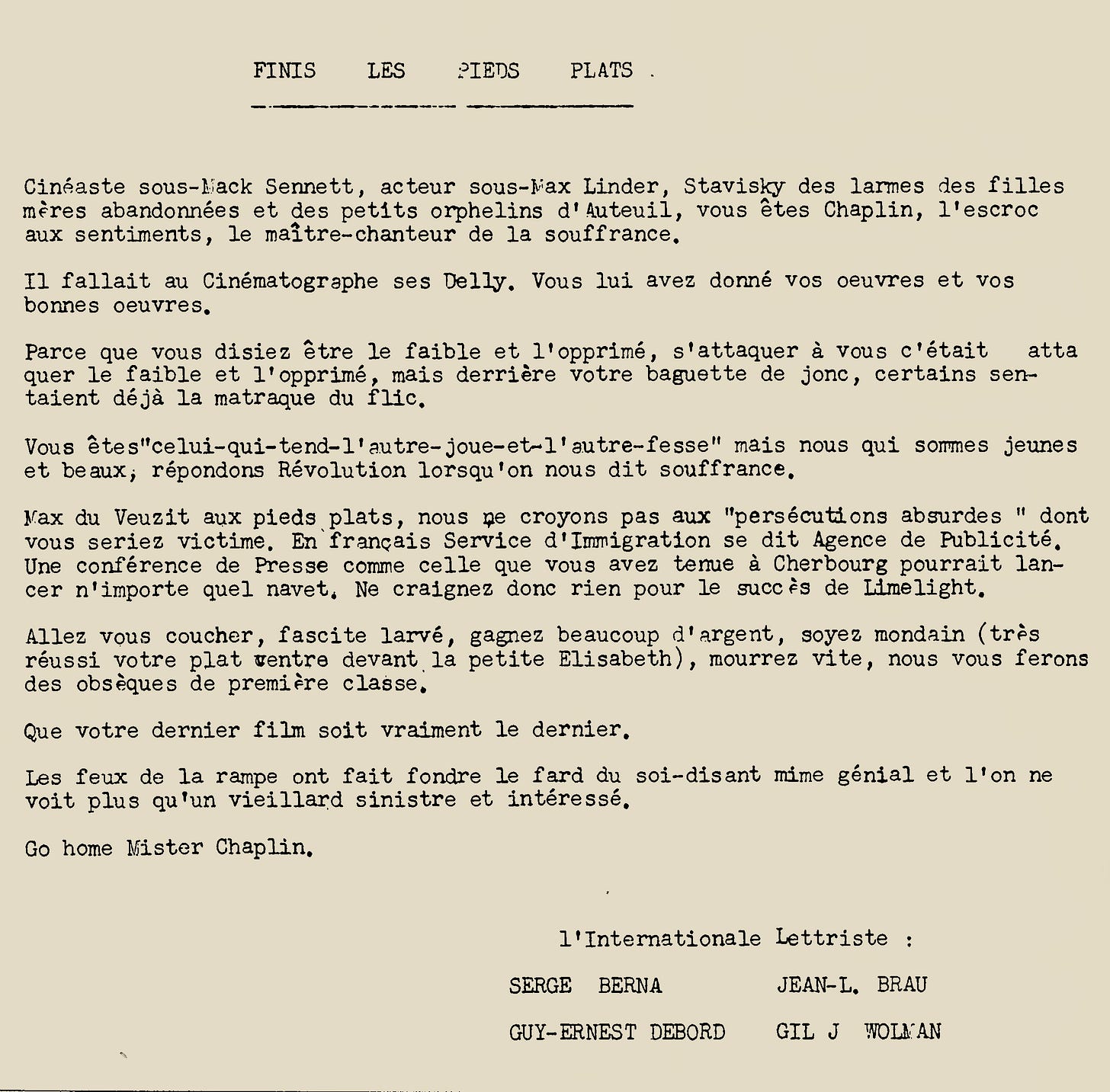

Finis les pieds plats/No More Flat Feet, the broadside issued by the Lettrist International on the occasion of the Limelight press conference. “Go home Mister Chaplin.”

I. “La poesie en vogue à St-Germain-des-Prés”

In 1955, the British television network ITV commissioned a twenty-six-part travelogue called Around the World with Orson Welles, in which the celebrated actor and director was to travel the globe reporting on developments in international culture for the incipient domestic TV audience. Welles, swimming at the time in half-finished and abortive film and theater projects, blew a series of deadlines and only managed to deliver six partial episodes filmed entirely in Western Europe, a far cry from the ambitious initial order. Still, the program contains a number of notable segments, including a fourth episode which takes as its subject the Paris neighborhood of Saint-Germain-des-Prés—ground zero for the existentialists, who were then drawing worldwide attention. The episode features brief glimpses of Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Jean Cocteau, but the actually notable interview is with a group whose members, though clearly all too eager to appear on camera, were also plainly out of step with the Sartrean hepcats (and, in fact, had long mixed with theorists who would soon be publicly referring to J.P. as an “imbecile”). The segment was on the poetic movement of “Lettrism,” and it starred the group’s principle English-speaking advocate, Maurice Lemaître, as well as its founder, the former street hooligan and all-time art lunatic Isidore Isou.

Episode four of Around the World with Orson Welles. The segment on Lettrism begins at 18:45.

The Welles interview begins with a title card (“‘LETTERISM [sic] is the latest way to express yourself poetically in St. Germain des Pres; it has to be heard to be believed”) before cutting to a public bookstore reading and a shot of Isou intoning a cacophonous series of rapid-fire sounds, joined at times by his acolytes Jacques Spacagna and Lemaître in a sort of chanting, phonetic unison.1 Afterwards, Welles interviews Lemaître, probing him about the “new letters” he purports to have discovered, particularly dopey examples of which (coughs, rhythmic lip pops, duck-like quacks) his subject readily provides. Next to a mute Isou (who didn’t speak English), Lemaître expounds on the roots of their proto-sound poetry, saying that he and his friend, “disappointed by surrealist poetry,” began writing using only letters to compose everything from poems to symphonies—an explanation that earns a hurried, incredulous look offscreen from Welles, and a quick request for another madcap performance.

The tone of the segment wavers somewhere between the slipshod feel of early television, Welles’s practiced self-seriousness, and a kind of implied triviality; though not explicitly mocking, there is a distinct “news of the weird” feel to the proceedings. The awkward mixture is typified in Isou’s hesitant presence as he nods along with Lemaître, smiling at the Hollywood star in his midst even while his once-vital, once-virulently oppositional movement is reduced to a two-minute curiosity for the at-home audience. After another few seconds of manic chanting, Welles, his mainstream pop-cultural imprimatur, and the viewer all move on to other things.

In fact, by 1955, Isou’s Lettrism was, nearly ten years after its initial founding, already far from the “latest” in Saint-Germain-des-Prés’s artistic circles, and every self-styled Parisian avant-gardist would probably have known so. Even leaving aside the existentialist crew, the true vanguard mantle had been usurped three years prior in a deft act of public splintering, one which hollowed the Lettrist movement’s very name of its significance, turning it into a byword for the outdated revolutionary methods of the initial postwar period. Isou’s Lettrism was, by now, known primarily as the launching pad for the L.I., or Lettrist International, the actionism-oriented, resolutely political art group centered around the young filmmaker-theorist (and onetime Isou protegé) Guy-Ernest Debord, whose use of new strategies in print and careful fanning of public scandal had quickly gained his faction and himself a degree of notoriety that far outshone Isou’s own.

That Debord would continue to refine his subversive tactics—culminating in his leading role in the Situationist International and their involvement, in turn, in the student and labor strikes of May 1968—is super well-known.2 But the Debord factions’s initial split with Lettrism, and the subsequent development of the L.I.’s revolutionary program—as the spurned Isou stewed in its growing shadow—have a lot to teach us about the evolution of the postwar avant-garde at large. Constituting a break in the lineage that entangled leftist resistance with prior artistic vanguards, the L.I.’s turn toward non-artistic scandal and agitation set the stage for the full-on revolutionary unrest of the 1960s and the countervailing violence of the 1970s, even as it employed and expanded on the avant-garde’s use of stunts and the burgeoning popular culture to achieve its ends. Isou’s status as a stymied artistic revolutionary, a link in the countercultural lineage reduced to a footnote in a better-known, more bankable art-historical narrative, is paradigmatic of the move away from early- and mid-twentieth-century methods of aesthetically-based resistance, and the attendant push into the realms of cultural maneuvering, discursive theory, and direct action that would come to define the new counterculture.

Which is to say: Isou’s apparent obliviousness in the Welles clip contains in it more than the palpable feeling of his work and its importance being lost in translation. The hesitancy and bewilderment on the poet’s face in 1955 could just as easily have applied to the entirety of the postwar avant-garde as it had existed up to that point: a cultural curio, still touting its influence though increasingly outmoded, midway between disregard and cooption (for proof of which you can see Sartre and Camus’s whole deal). And though this power struggle would go well beyond the French context,3 its formative incarnation was felt in a Paris caught between the inherited tactics of Dada and Surrealism and the new, more aggressive avant-garde generation on the horizon.

Guy Debord in Cannes, 1951, where he’d meet the Lettrists and attend the premiere of Isidore Isou’s Traité de bave et d’éternité.

II. The creative act

It is no accident that the mid-1950s avant-garde shifts toward more explicitly destructive political measures should have shocked the artist class of the initial postwar period. This was a crew whose members had, after all, been afflicted by the state violence in ways that Debord’s younger generation had just not been. Like the founders of Dada and Surrealism before him, Isou emerged as an artist in the immediate aftermath of an indescribably hellish epoch of war, and no matter the bombast and pretensions to countercultural mayhem he imbued in the DNA of early Lettrism, the extent of the bloodshed, the still-fresh memories, and the gravity of the calamity through which the continent had just passed all seem to have exerted an influence on his developing a revolutionary practice in which creation was the primary goal.

Born Jean-Isidore Goldstein in 1925, Isou (like Dada’s founder Tristan Tzara, a Romanian Jew) had weathered enough in the way of culturally-dictated bloodshed and repression by the time he arrived in Paris in 1946. His experience of the Holocaust, in its horrific Romanian context, is a story for another time, but the fact of the matter is: he barely survived. And though once in Paris, Isou’s Judaism and its implications would get tangled up in the other reference points for his creative output (as in the momentary flash of a star of David scratched into the celluloid of Traité de bave et d’éternité, the first Lettrist film), Nazism would remain a reference point for the rest of his life, along with “neo-Nazi,” eventually his favorite epithet for Debord.4

The ties between the artistic and political vanguards at large were also made murky by the war. Gabriel Pomerand, the early Lettrist who met Isou at nineteen in a Paris soup kitchen for Jewish refugees, had spent the war years and his teens in service of the Resistance in Marseille, and in spite of a talent for scandal and a pronounced love of the Comte de Lautréamont and other proto-countercultural writers and artists, Pomerand’s knack for anti-mainstream provocation couldn’t and wouldn’t erase his connection to wartime politics; the Resistance had been his reality, and his mother had died in Auschwitz. Similarly, a certain romantic idealization of veteran partisans dominated French postwar progressive society: the French Communist Party trumpeted its resistance credentials even as right-leaning collaborationist elements remained in power, and once-staunchly left-wing cultural voices (like the formerly underground newspaper Combat) drifted toward the center.5 The Lettrist term for the unholy amalgamation of the prevailing intellectual trends in Paris—Résistentialisme—is a good indicator of the conceptual monolith they believed they were up against.

It’s pretty unsurprising that Debord, for whom the postwar was “an essential crisis of history,” would put the political ineffectuality of the late-1940s avant-garde down to its willful alignment with previous countercultural movements, lambasting the “sterile retreading of steps inherited from [idealized] historical avant-gardes,” ill-equipped to speak to the contemporary situation. And sure, Debord (referring in large part to Isou and Lettrism’s early provocations) is correct that early Lettrism had profound artistic ramifications but few political ones.67

What Isou lacked in direct revolutionary efficacy, however, he made up for in cultural vitriol, in a brazen, kill-your-idols iconoclasm, and in the reliably avant-garde instinct for marketing. Before we go on, it’s important to underline the singularly extreme quality of Isou’s forcible push into the Paris avant-garde. The dude arrived in town with the literal and explicit intention of becoming an art star, and no other revolutionary blowhard—not Tzara, not André Breton, not Debord himself—demonstrated a comparable monomaniacal streak. Seriously, nobody comes close.

After landing in Paris with his manuscripts and making straight for the offices of Éditions Gallimard, Isou bullied his way into a meeting and a provisional acceptance of his texts.8 In a further bit of cultural piggybacking, Isou then set up shop in the same Saint-Germain cafés that had nourished the growth of the existentialists, from which they got to work proclaiming the importance of their poetic discoveries and calling poorly attended “conferences” to inform the public. But it was Isou’s first Lettrist stunt, four months after he arrived in France and linked with Pomerand, that best confirms his reliance on tried-and-true avant-garde tactics: a patricidal hit on Dadaist founder Tristan Tzara.

Tzara was, by all accounts, Isou’s idol. Which, naturally, is what necessitated his attendance of a January 1946 performance of Tzara’s play La fuite, presented by former Surrealist Michel Leiris and counting the author in attendance. Midway through Leiris’s introduction, Isou, Pomerand, and the crew of Lettrist flunkies whom they’d provided with tickets stood up and began shouting the speaker down. “Monsieur Leiris,” Isou called, we know about Dadaism... talk to us about a new movement, like Lettrism, for example.” Leiris, who replied (very funnily) that he had never heard of Lettrism, was soon sharing the stage with Isou, who commenced a breakdown of his new poetry’s relative merits as Tzara looked on with confusion and the audience jeered.9

That Isou and Pomerand’s public embarrassment of their forebear constituted more of a rehash than a rejection of the provocations of Dada and Surrealism didn’t detract from its being good publicity; indeed, the incident was dutifully reported on in Combat and other leftist journals, and seems to have become the talk of the Left Bank. Of similarly dubious originality was the content of Lettrism’s poetic program itself—that where Dada had separated words from phrases, Isou’s movement sought to separate letters from words. In reality, the “non-conceptual organization of letters or phonemes considered in their pure state” advocated by Isou as a break from Dada was surely indebted to Tzara and Hugo Ball and other members of that selfsame movement.

Still, there was meat on the bones of Isou’s theory, and its eventual capacity to attract monumental talents like Debord and Gil Wolman is testament to the major contribution it made to the postwar scene. Lettrism’s conceptual basis was predicated on the tendency for new forms to undergo periods of amplification (in which their parameters are expanded, taking on greater and greater relevance in art and life) and décomposition (in which they wither into gesture and banality, leaving behind hollow signifiers). In lieu of these cyclical phases, Isou proposed ciselure, a “chiseling,” wresting the earmarks of a given form from their conceptual resting place before they have a chance to calcify and turn self-referential. And while Dada and Surrealism had done plenty of formal and conceptual chiseling and rearranging, the application of the technique to letters and phonemes (and, soon enough, to film and sound) certainly constituted a step further than anything Tzara or Breton had dreamed up. Less a total rejection than a refinement, perhaps, of prior artistic aims, Isou’s Lettrism was an advancement in any case; and in its fundamental privileging of the creative act above all, it constituted a definite alternative to the Résistentialiste morass in which both the avant-garde and the left intelligentsia had become entangled.10

Having managed to make a name for itself and depose the Saint-Germain old guard with its initial salvos, Isou’s Lettrism cemented its hold on the scene with numerous recitals and weekly readings, attracting adherents and gathering steam. General provocations continued to be a stock in trade, with the transgression of good taste a goal in itself: Isou’s gang dyed their hair, wrote on their clothes, and made a point of staggering around drunk.11

But their target didn’t train itself on the larger cultural field with any real specificity, which is why a much greater scandal attended the hijacking in April 1950 of a televised Easter service (“the Notre Dame Affair”), during which four Lettrists, members of the group’s burgeoning “actionist” wing, took to the pulpit of the best-known church in Europe and preached a blasphemous High Mass (“God is dead; we vomit the agonizing insipidity of your prayers... we proclaim the death of the Christ-God, so that Man may live at last”).12 The scene at the cathedral ended unsurprisingly in chaos and arrests, a new level of infamy for Lettrism, and a condemnatory response and vigorous months-long debate in the pages of Combat (including a note of support from André Breton, who wasn’t gonna miss the party). The blasphemous text had been written by the twenty-five-year-old Serge Berna without the involvement of Isou or other original Lettrists (though Pomerand had been in attendance), prefiguring the schismatic founding of the breakaway L.I., with Berna as a member, two years later.

On the Isou side of the split, the agitational tactics always been primarily about self-promotion, and they continued in that vein. The most impactful of these incidents was scarcely noticed in comparison with the Notre Dame scandal (which Isou hastened to condemn, having had nothing to do with the “action”), but its effect was as decisive in splitting the Lettrists. This was the 1951 Cannes premiere of Traité de bave et d’éternité, which Isou brought to the festival himself to have screened. The film, a dizzying collage of scratched-up found footage, broadly theoretical voiceover and asynchronous sound, only played partway before the picture cut out, leaving the discomfiting soundtrack to play against a blank backdrop.13 The abortive screening shocked the staid festival audience, but perhaps more fatefully, it confirmed the interest of a nineteen-year-old student by the name of Guy Debord.14

Original trailer for Traité de bave et d’éternité.

III. An end to “aesthetic action”

Debord’s retrospective criticisms of the tactics of early Lettrism have their merits as inquiries into the efficacy of art-inflected techniques as a means of political resistance, but they elide the profound similarities between Isou’s strategies and the ones initially employed by Debord and his circle themselves. While Lettrist International and later Situationist theory would develop over the next fifteen years into a discursive tangle as idiosyncratic and knotted as any on the leftist intellectual landscape, Debord’s first years as an artist-revolutionary came straight out of the Isouian playbook. There was a formally jarring, asynchronous film (1952’s Hurlements en faveur de Sade, comprising a voiced soundtrack against a blank screen), a pronounced and public emphasis on delinquency and drunken transgression, and a coming out party in the form of a raucous public spectacle.

The principal target of “l’Affaire Charlot” may not have been as close to the mainstream French soul as a Catholic Easter mass, but his privileged status among leftists made his victimization a cause for outrage within a new circle: the political vanguard. In October 1952, Charlie Chaplin, persona non grata in his adopted United States due to his widely-suspected Communist sympathies, came to Paris’s Ritz Hotel to promote his film Limelight and be fêted by the friendlier French media establishment. He hadn’t even made it into the press conference, however, before the entrance was blocked a gang of provocateurs (Debord and Berna as well as Gil Wolman and Jean-Louis Brau) who shouted slurs and tossed tracts into the crowd excoriating Chaplin, calling him a “budding fascist,” and imploring him to “Go home Mr. Chaplin.”15

The broadsheet was signed by the four members of “The Lettrist International”: Debord and Wolman had founded the group in secret months earlier. The new appellation was meant simultaneously to parody the Stalinist “Third International” even as it lent a tinge of political revolutionary potential to ye olde lettrisme. Isou hastened to distance himself from the attack on Chaplin in a letter to Combat (he would later deride it as “confusionniste,” also a classic insult of Debord’s) but he couldn’t undo the association with—or prevent the cooption of—the Lettrist brand. The new name, like the action itself, was meant to signal an attack both on the bourgeois socialism of the French left and on bureaucratic state Communism. In going after Chaplin, Debord and his faction announced themselves as willing to slaughter the sacred cows not of the artistic avant-garde, not even of the religious French mainstream, but of the progressivist left. As an inevitable side effect, early Lettrism’s all-important creative act (and all the self-aggrandizing art-world hijinks that went toward its full expression) had undergone its first of many oustings, to be replaced eventually by direct political engagement.

And naturally, according to the perfect Shakespearean logic of the artistic avant-garde, such a development could only be followed by the ousting of the creative act’s principle advocate: in an open letter written by Brau on November 3, 1952, Isou—Tzara’s heir in more ways than one—was denounced as “unnecessary” to his own movement and, days later, formally and stunningly “excluded” from the ranks of the Lettrists.16

You’d be forgiven for being rocked by the irony of all this. That icon of postwar art agitation, always so insistent on being situated in opposition to previous movements, was undone by that very insistence; in pursuing any relation with previous art vanguards (even a negative one), the L.I. argued, Isou was woefully limiting his movement’s revolutionary potential. The time had come for a shift in emphasis away from art toward the possibilities obtainable in the larger postwar social and economic spheres, a dawning culture of revolutionary opportunity that Isou—too caught up in aesthetics—had missed. “Our era has arrived at a level of knowledge and technical means to make the construction of any style of life possible... only the contradictions of the present economy slow their application,” as Debord would put it, in a 1955 edition of the L.I. periodical potlatch. “It’s the existence of these possibilities that condemns aesthetic action, outdated in its ambitions and its powers, just as the mastery of natural forces has condemned the idea of God.”17

Isou, Gabriel Pomerand, and Jean Cocteau, Paris 1950. Jean-Michel Mension: “I feel it would be interesting to extract the avant-garde kernel from Isou’s thought: the issue of ‘externality,’ the issue of youth revolt, the sense that youth was going to play a different role in the period then beginning--all perceptions that were very much ahead of their time. But I think that as an artist Isou was not very talented; he wasn’t a good painter.”

IV. “The great river of total forgetting”

The early years of the Lettrist International have been studied primarily in their capacity as a testing ground for the theories and practices that would form the basis for the better-known Situationist International in the ensuing decades—and, as key S.I. concepts (psychogeography, the construction of situations) and techniques (the dérive, détournement) were laid out and developed during this time, this focus is obviously not unreasonable. Still, the first steps of the L.I. are just as notable for the way they synthesized and reflected back the efforts of prior would-be revolutionary groups—with avant-garde artists, naturally, among them, in spite of any anti-aesthetic trumpeting. For even if, as Ivan Chtcheglov wrote in the foundational 1953 L.I. text Formulaire pour un urbanisme nouveau, “everybody wavers between the emotionally still-alive past and the already-dead future,” that past was still detectable in the basis for every revolutionary conception advocated by the group.

Take psychogeography, the area of inquiry reflecting the L.I.’s increased emphasis on the transformational capacities present in civic economies—particularly as expressed through urban architecture and workaday life. Formulated a scant five years after Isou plastered the Latin Quarter with leaflets invoking youth in the street, Chtcheglov’s “new urbanism” made the essential step of matching a practical, quotidian technique (the dérive, Debord’s calculated urban drift) with the lofty revolutionary conceit, but it also functions as a tweak on existing avant-garde conceptions—from the flânerie of the Decadents and Surrealists to the ville radieuse of Le Corbusier.18 Similarly, the détournement used by L.I. members to subvert and recontextualize cultural signifiers has been understood as an effort at bridging the negatively- and positively-oriented context-shifting techniques used by Dada and Surrealism, respectively. Though Debord’s faction widened the application of art techniques to larger cultural milieux, invoking labor and class and actively critiquing the non-artistic left, they still couldn’t help but recall “mainstream” avant-garde tradition.

Unsurprisingly, one of the figures most keen to point out the contradictions in Debord’s radical program was the marginalized Isou, who endured taunts from his onetime protegé and watched as Debord’s new strategies gained traction through the 1957 advent of the Situationist International, even as he continued to operate as a self-proclaimed Lettrist (albeit one culturally-amenable enough to appear in Orson Welles documentaries).19 For Isou, Debord’s elaborate techniques masked a nihilistic fixation on leisure and social standing in lieu of culture: “My adversaries don’t seek to attain an empirical or cultural goal, more preoccupied with a certain communal ‘farce,’ a promiscuity of friendly relations and tastes.”20 Isou, the great advocate of ciselure—the artist who sought to chip away at forms until nothing but the most essential remained—saw a miserable outcome in Debord’s application of that same nothingness to the non-artistic realm, to a place where the éternité of his landmark Lettrist film could have morphed into the cruder NE TRAVAILLEZ JAMAIS (“Never work”). The L.I./Situationist “revolutionary struggle without science and theory,” its blind allegiance to “a worker’s revolt that is anti-culture,” all of its theoretical reductivism added up, for Isou, to a néant aggressif, an “aggressive nothingness” that bore more in common with fascism than with revolution, that distracted from important cultural work, that deadened and zombified its followers. “Night-night, Situationists! Dérivez, dérivez!” Isou wrote in 1960. “The great river of total forgetting lies ahead. And don’t reawaken too early, because the awakening is sad.”

Though it comes cloaked in the usual all-or-nothing avant-garde fulminatory style (and is, for the record, 100% rooted in personal bitterness rather than some highminded political critique), Isou’s criticisms still take on a nuanced and trenchant dimension when considered in view of the changing avant-garde tactics of the day. In their appeal to revolutionary sentiment outside of the cultural vanguard, the L.I./S.I. did risk turning altogether anti-culture. And indeed, after a few more years of internecine squabbles within the Situationists on the subject, Debord would make the controversial move of forcing out all of the group’s artists, leaving only his theoreticians’ wing to plot the revolution. But more fateful still was the ambitious reorientation of avant-garde resistance away from the experimental fringe and toward the culture at large. In their toppling of “aesthetic action” and other techniques of the past, Debord’s clique opened the avant-garde revolutionary impulse up to all the complications, cooptions, and chaos that postwar culture—its geopolitical tensions, its emergent media and its nascent “pop” component—could visit upon it, for better or for worse. In the ensuing large-scale protest movements that rocked much of the west in the latter half of the 1960s, the “total forgetting” presaged by Isou would be carried out via the application of increasingly decisive and violent takes on the questions of theory and praxis introduced by the Lettrist International.

The shift was decisive, even if its beginnings had seemed innocuous, or at least indistinguishable from what passed, in the scene, for business as usual. As Jean-Michel Mension put it: “Isou was not a scoundrel, he was a nice guy. In the first place, he was completely mad, but at the same time he was a very serious person—he didn’t drink—with his feet firmly on the ground. He was quite convinced, however, of his own genius. Later on, he resented Debord for pinching his position as leader. But that occurred on much more of a political basis than an artistic one.”

.·:'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''':·.

: : .x+=:. .. : :

: : z` ^% . uW8" : :

: : . <k x. . `t888 : :

: : .@8Ned8" .@88k z88u 8888 . : :

: : .@^%8888" ~"8888 ^8888 9888.z88N : :

: : x88: `)8b. 8888 888R 9888 888E : :

: : 8888N=*8888 8888 888R 9888 888E : :

: : %8" R88 8888 888R 9888 888E : :

: : @8Wou 9% 8888 ,888B . 9888 888E : :

: : .888888P` "8888Y 8888" .8888 888" : :

: : ` ^"F `Y" 'YP `%888*%" : :

: : "` : :

: : .x+=:. : :

: : z` ^% : :

: : . <k .u . : :

: : .@8Ned8" . .d88B :@8c : :

: : .@^%8888" .udR88N ="8888f8888r : :

: : x88: `)8b. <888'888k 4888>'88" : :

: : 8888N=*8888 9888 'Y" 4888> ' : :

: : %8" R88 9888 4888> : :

: : @8Wou 9% 9888 .d888L .+ : :

: : .888888P` ?8888u../ ^"8888*" : :

: : ` ^"F "8888P' "Y" : :

: : "P' : :

: : . .. : :

: : @88> . uW8" : :

: : %8P `t888 : :

: : . 8888 . .u : :

: : .@88u 9888.z88N ud8888. : :

: : ''888E` 9888 888E :888'8888. : :

: : 888E 9888 888E d888 '88%" : :

: : 888E 9888 888E 8888.+" : :

: : 888E 9888 888E 8888L : :

: : 888& .8888 888" '8888c. .+ : :

: : R888" `%888*%" "88888% : :

: : "" "` "YP' : :

'·:............................................:·'Sic it or ticket: the name of the movement is rendered variously in English as either “Letterism” or “Lettrism.” In the interest of hewing closer to the original French, I’m going with the latter spelling.

Enough that it features heavily in the historical backdrop for Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake, which I went in on a few months ago.

Here and throughout, I am majorly indebted to Andrew Hussey’s Speaking East: The Strange and Enchanted Life of Isidore Isou (Reaktion, 2021), McKenzie Wark’s The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International (Verso, 2011), and James Trier’s Guy Debord, the Situationist International, and the Revolutionary Spirit (Brill, 2019).

As seen in, for example: the 1947 French elections, which precipitated a dispute in Combat’s editorial ranks that saw the paper sold and the resignation of longtime editorialist Albert Camus. In Olivier Todd, Albert Camus: A Life.

From Debord’s Rapport sur la construction des situations (translation Ken Knabb): “Lettrism, in France, had started off by totally opposing the entire known aesthetic movement, whose continual decaying it correctly analyzed. Striving for the uninterrupted creation of new forms in all domains, the Lettrist group carried on a salutary agitation between 1946 and 1952. But the group generally took it for granted that aesthetic disciplines should take a new departure within a general framework similar to the former one, and this idealist error limited its productions to a few paltry experiments.”

This wasn’t for lack of trying, though: In 1948, Isou wrote the broadly political Treatise on Nuclear Economy: The Youth Uprising, and plastered the Latin Quarter with tracts predicting that “Twelve million youth will descend into the streets for the Lettrist revolution.” While making the key step of identifying la jeunesse—youth qua youth—as a revolutionary category, the texts had little practical effect, though they would eventually figure prominently in Lipstick Traces.

The full story—at least as filtered through Isou’s self-aggrandizing legend and recounted in Hussey’s Speaking East—is incredible. It was early enough in the morning that the editor whom Isou had hoped to meet, Jean Paulhan, wasn’t in yet, but when he heard that Gaston Gallimard was in the building, he bullied his way into a meeting and thrust the pages of his manuscript, L'Agrégation d'un nom et d'un messie (“The Making of a Name and of a Messiah”) into the publisher’s hands.

Again, check out Hussey’s Speaking East for more on this, and also Marius Hentea’s TaTa Dada: The Real Life and Celestial Adventures of Tristan Tzara (MIT, 2014).

Lest it get lost in all the self-promotional bombast, it should be noted that Isouian Lettrism was enormously impactful artistically, particularly in cinema: Stan Brakhage credits a viewing of Isou’s Traité de bave et d’éternité with kickstarting his interest in the form, and wrote Isou numerous grateful letters to that effect. Early screenings were also championed by Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Godard. For more check out Kaira M. Cabañas, Off-Screen Cinema: Isidore Isou and the Lettrist Avant-Garde (UChicago, 2014).

IMO this was as much an art provocation as an extension of the Romanian huligan subculture from which Isou had emerged, itself a sort of mash-up of enfant terrible snottiness and actual Brit-style soccer hooliganism. In the 1930s, Romanian huligani had been noted for, among other things, talking crazy shit on anyone old enough not to have been born in the twentieth century. Zoomers, maybe take a page from this?

Kushner also refers to this event in Creation Lake, though she gives credit to Debord, who wasn’t actually there.

I’ve read various explanations for this, but Hussey says that the film just wasn’t finished in time for the screening.

Isou himself wrote that he didn’t know whether or not Debord was at the initial screening, but that the latter’s subsequent film work would suggest a familiarity with the circumstances of Traité’s premiere. Debord, for his part, was absolutely clear that he was in attendance, and he worked to organize further screenings in the fall of 1951.

According to Jean-Michel Mension in The Tribe, Chaplin’s actual offense was the acceptance of a medal from the chief of police (probably the Légion d’Honneur, which he’d received twenty years prior). Mension: “We had to demolish Charlie Chaplin, but it was a directly political issue.”

Debord in Rapport sur la construction des situations: “In 1952 the Lettrist left wing organized itself into a ‘Lettrist International’ and expelled the backward fraction.” Needless to say, Isou would go on using the name, accusing the L.I. of co-option.

Guy Debord, potlatch #19, 1955, in the English translation from Ken Knabb’s Situationist International Anthology. My italics.

Also, as has been discussed elsewhere, the dérive was also just a practical adaptation to the meandering and drinking and hitchhiking Debord and his crew were already doing. Mension: “My first derives were with Guy, Eliane, and Eliane’s girlfriend, Linda. It was simple: we started hitchhiking, and the fourth or fifth car would pick us up. Guy would buy bottles of wine from a cafe, we would drink them, then set off hitching again. We went on like that until we were completely potted. Not all that poetic, really.”

From Debord’s 1954 letter to “My poor Isou”: “On both the mental and financial planes, you are, precisely, shabby.”

The Isou quotes in this paragraph come from his 1960 essay, “L’Internationale Situationniste, un degré plus bas que le jarrivisme et l’englobant,” which I got my hands on via the collection Contre l’Internationale Situationniste. My translation.