When I started tinkering with the idea of starting a Substack last fall, it was solely for the purposes of writing the following piece: a long essay on Rachel Kushner’s new novel Creation Lake, threaded with lengthy digressions on the author’s previous work, the book’s historical/political contexts, and lots and lots of minutiae on the Situationist International. I didn’t think the piece would a) take me this many weeks to write, or b) that it would end up lengthy enough to trigger the “Post too long for email” Substack popup warning, but here we are.

Having broken the seal, I’m planning on doing one of these--that is, a literary review with a lot of extraneous junk--every once in a while. If anyone has ideas on books that might withstand that treatment particularly well, lemmy know.

Until then, here’s the piece on Creation Lake, but n.b.: while there isn’t a lot of plot discussion ahead, I suppose it’s still technically true that spoilers follow, so if you haven’t read the book and want to do so, take some responsibility for your own happiness on this one. Also--from the primary documents department--shoutout to NOT BORED and Bureau of Public Secrets, whose work translating the texts and correspondence of Debord and the Situationists I’ve been piggybacking on for years now.

Next week, something way mellower, promise.

𝖙𝖎𝖑 𝖙𝖍𝖊𝖓,

Mark

The Situationist International in 1962. From Creation Lake: “Bruno Lacombe had known Guy Debord well, or as well as anyone could have known him, moody and dickish as he seems to have been.”

When Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake was published at the end of August, the big reviews I read all seemed eager to make hay out of a brief scene from early in the book in which the narrator—an undercover operative for hire with the cryptonym of Sadie Smith—takes a piss in the woods along a highway in southern France and sees a discarded pair of cheapo panties, “Day-Glo-orange underpants snagged in the bushes at eye level.” The critics cited the passage approvingly, but I also remember seeing responses, on Twitter/Bluesky/wherever, ridiculing it—for its hyper-confident affect, its didacticism, for the way it leverages the appearance of the panties to launch into a lengthy disquisition on the workings of the free trade Eurozone:

The real Europe is not a posh café on the rue de Rivoli with gilded frescoes and little pots of famous hot chocolate . . . the real Europe is a borderless network of supply and transport. It is shrink-wrapped palettes of superpasteurized milk or powdered Nesquik or semiconductors. The real Europe is highways and nuclear power plants. It is windowless distribution warehouses, where unseen men, Polish, Moldovan, Macedonian, back up their empty trucks and load goods that they will move through a giant grid called ‘Europe,’ a Texas-sized parcel of which is called ‘France.’ These men will ignore weight regulations on their loads, and safety inspections on their brakes. They will text someone at home in their ethno-national language, listen to pop music in English, and get their needs met locally, in empty lots on mountain passes.

For my part, the scene made me think of the opening sequence of Claire Denis’s No Fear, No Die, in which Dah, Isaach de Bankolé’s character, meets up with his buddy Jocelyn, played by Alex Descas, along a similarly desolate stretch of French highway. Jocelyn (who’s originally from Martinique) has just ridden up in a Spanish tractor trailer that’s carrying the illicit shipment of roosters he and Dah (who’s from Benin) are gonna use to set up a gnarly cockfighting ring in a Paris banlieue. Valencia, Martinique, Benin, Paris; all waystations on the trade route, all nodes on the distro network. In case it’s not heady enough, Denis gives us a final nudge as to the vast dimensions and generational legacies of global trafficking—of goods, of contraband, of human beings—when Jocelyn gets in the car, and Dah puts on a tape of Bob Marley doing “Buffalo Soldier,” and the two men wordlessly vibe out.

So yes, to make hay: the Creation Lake roadside scene is certainly flashy and provocative writing, a minute itemization of a supermassive and intractably problematic situation, pitilessly elaborated and brusquely simplified all at once. Like the scene in No Fear, No Die, it charts a world in which half-remembered nationalisms and the human beings they constrain are ingested into cozy Schengen zone commodity relations, all-but-undetectably, or sort of undetectably, or undetectably except for when a reminder snags on a poke of greenery. Kushner’s is grosser and less overt, perhaps, than the scene in the film, but then, so is the liberal condition it describes relative to the one that predominated in 1990, when No Fear, No Die took place.1 And if Kushner’s lecture doesn’t operate on the same quietly gestural, almost elemental plane as Denis’s does, that just serves to underline the plasticky shrillness of the current economic arrangement, the overstuffed and pervasive and shitty materiality of our lives under it. In its outsider’s presumptuousness, its on-high vantage, its apparently effortless judgment, the scene is loud and rude and exactly as offensive as its detractors claim. Which is to say, it’s vintage Rachel K., and it’s great.

But the Eurogrid/Nesquik spiel also points to what’s particularly interesting and weird and, I think, somewhat tragic about the book: namely, its deep interest in enumerating the symptoms of our present sickness, and the attendant limits on its capacity for imagining a cure for the sickness itself. Creation Lake is replete with chapter-length digressions, essayistic walkabouts, plotting that’s loose then tight as hell then loose again. This structure yields plenty of opportunities for Kushner to display her usual gifts for clarity and distillation, her risky habit for hitching characters to major historical figures/movements/artworks, her incorporation of heavy research and a political longview that’s legibly leftist (if deeply bruised). But amid all the excess, all the catalogues and pronouncements and prognoses and zingers and bons mots, all the palpable pleasure the author takes in doing the stuff that bums some readers out, she also does something that kinda bums me out, which is that she seems to settle, to retreat.

The result is a super smart book that willfully avoids paying off the full depth of its intelligence, a supremely confident book that has the feel of shrinking from its own implications—or at least of contenting itself with only the easiest, most surfacey among them. It’s as if the book, given the choice between a deep dive into the thematic and narrative subtleties of its rich historical/political setting and a more mundane sort of fish-in-a-barrel satire of them, has tended decidedly towards the latter. Still, the results are effective, hard to fault on their face, and (as in the highway scene outlined above) just as “true” for their relative lack of ambition.

Which is why it’s particularly tough for me, a reader who obsessively splashes around in many of the same historical eddies as the author, who believes ardently (like, to a legitimately annoying degree) in the capacities of fiction to bring those histories to a kind of life, and who thinks of Kushner as one of our most interesting novelists, to make sense of Creation Lake. For those of us who endeavor to create work about subculture, historical avant-gardes and, and especially, revolutionary politics, the book might function like an object lesson. No out-and-out success for my money just as it’s no simple failure, Creation Lake feels, mostly, like a study in tradeoffs.

Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed from 1970. “For nine-tenths of human time on earth people went underground. Their symbolic world was formed in part by their activities in caves, by modalities and visions that darkness promised. Then, this all ceased. The underground world was lost to us.”

So then, why write about it? One reason off the bat: I’m a big fan of Kushner’s, straight up. Though I feel differently about each of her books and have faves and non-faves and all that, I really admire her larger project, her inquiries into the experiences of individual women inside unfailingly alienating (and unfailingly male) systems of value and control, her interest in and critique of the historical left, her allusiveness and ambition and deft mix of high and low. Also, on a level that’s harder to explain—but which definitely has to do with her taste for characters who are loudmouths, radicals, lowlives, psychos—you just sort of feel that Kushner gets it, so that, whatever this says about me, I just kinda find myself celebrating her success, the fact of her popularity, for its own sake; like, it’s easy to feel dubious about every single solitary component of modern literary publishing and its promotion, and I do, but I also can’t help but think it’s sick that a novelist whose books attempt to grapple with Debord and Morea and Kaczynski and Sanguinetti and Marinetti is also one of the ones getting the front page Book Review writeups.

I’ve seen Kushner catch a lot of shit, though, for some of these same tendencies—for seeming to engage glibly with the people or movements she references, or really, for seeming to namedrop (like when Frederick Seidel freaked out about a reference to Morton Feldman in The Flamethrowers, which was admittedly a little weird). And I get, for the record, that this critical discomfort is not some light kneejerk thing, that the careless leveraging of important marginal ideas is exactly the process by which those ideas get turned into hollowed-out signifiers (what Debord, for his part, would have called récupération), that it’s a slippery slope to a kind of smoothed-over pop leftist world of revolutionary gestures and, whatever, Robert Smithson earthworks and fast motorcycles and book club badges. I have a friend who finds it extremely suss, for example, that Kushner’s afterword to the reissue of David Rattray’s How I Became One of the Invisible doesn’t hardly get into Rattray’s work and is concerned mostly with how he was friends with her parents, which, obviously, fair enough. Ditto for the folks who begrudged The Flamethrowers its mildly Gumpian construction, its million cameos and jetset militancy and Soho scenester stolen valor.2 The novel’s apparently easy posture of fluency, across so many disciplines, can—it’s true—start to wear, to seem a bit facile, even a bit bad faith-y.

But also: The Flamethrowers completely ripped, and this excess, this breadth and audacity that everyone had gotten all up in arms about, was (in addition to the almost indecently kinetic prose and the juicy plot in which everyone sleeps with everyone) obviously part of what I found so impressive and inspiring in the book. It’s also important, I think, to note that it wasn’t just the presence of the historical fantasia vibe to which I responded. The novel also did something very specific with its vast reference base, which is that it used it to furnish several really rich characters, unfailingly lively, sufficiently contradictory figures whose complexities are both reinforced by and defined in opposition to the story’s glitzy historical trappings. I remember being so psyched, for instance, on the narrator Reno’s friend Giddle, the waitress whose previous association with the Warhol Factory mostly serves to underline her commitment to her present “life practice.”3 Giddle’s art is waitressing, and she insists she hates those snooty Factory girls, and it’s a testament to her characterization that she can embody, for Reno and for us, all the glories of this liberatory reframing of the creative act as well as all the tragedy of its deferred honor and lowly status, of the fact that it’s an obvious rationalization for a kind of failure. In other words, the subtleties and richness in Giddle’s character—and Reno’s, by extension—feed and are fed by the wellspring of artistic considerations that flow out of the novel’s high-concept setting, manifested not least in its cast of downtown legends. If the attendant questions of art/fame/underground culture constitute the kind of stuff you like thinking about, Kushner’s is a narrative system of intoxicating potency, but in this case it’s also built quite plainly on her brazen willingness to anchor us to, of all the well-trod cultural milieux, the Warhol Factory.

One more Flamethrowers example while I’m here. Reno, watching late night TV in New York, realizes that the 3:00 a.m. movie, Barbara Loden’s Wanda, is one she’d already seen in the theater with her shitty artist/industrialist boyfriend Sandro. On its face, this scene is a perfect thing for a reviewer to get all pissy about: after all, did people, even hip downtown types, really go see Wanda when it first came out? Even if they did, is it maybe a little convenient that this eventual signifier of rarefied cinephiliac good taste should be depicted as airing on, like, regular-ass rabbit-ears Manhattan television? Maybe, I don’t know, but you, reader, can choose to stress out about it, or you can luxuriate in the story moment, which is worth the buy-in. To wit: as Reno reflects on Loden’s pretty title character, “a person quietly letting her life unravel,” someone “driven to destroy herself, and because of her beauty, free to do so,” she remembers that Sandro—with whom she’s just had an argument lined with all sorts of unspoken tripwires about sex and power—had taken the film’s bleak Rust Belt setting as its primary point; “the stark life in a coal mining town.” Reno, on the other hand, knows that the film “was about being a woman, about caring and not caring what happens to you. It was about not really caring.”

Could Kushner have achieved what this scene achieves—the subtle referendum on the viability of Reno’s relationship, as well as the more general codification of the mess of dubious motives and bad options offered all alienated individuals under exploitative systems—without the encoded allusions to Loden, to coal country, to Wanda? Could the reader have been trusted to infer the same softly heartbroken point Reno is making about herself, to intuit the same hints about where she’s headed? Impossible to say, obviously. But it seems likely that, in this hypothetical version of the scene or its equivalent (or some weird “thinly veiled” exercise, least satisfying of all), we’d at best have lost some of this richness, some of this connectivity; our sensors wouldn’t light up, and if we happened to have our own memories of or relationship to Wanda, any associated store of feeling, we’d have no reason to draw from it. So yes, it’s super risky to go for it, to play “spot the reference” with your readers, to goad their in-group sensitivities, to invite the ungenerous reading that says you’re cynically leveraging others’ artwork or fame or ideas. But when your story demands you go for it? When the alternative is a scene that’s, sure, unobjectionable from the standpoint of scene politics, but impoverished on the level of emotional truth? In that case, it’s just as risky not to.

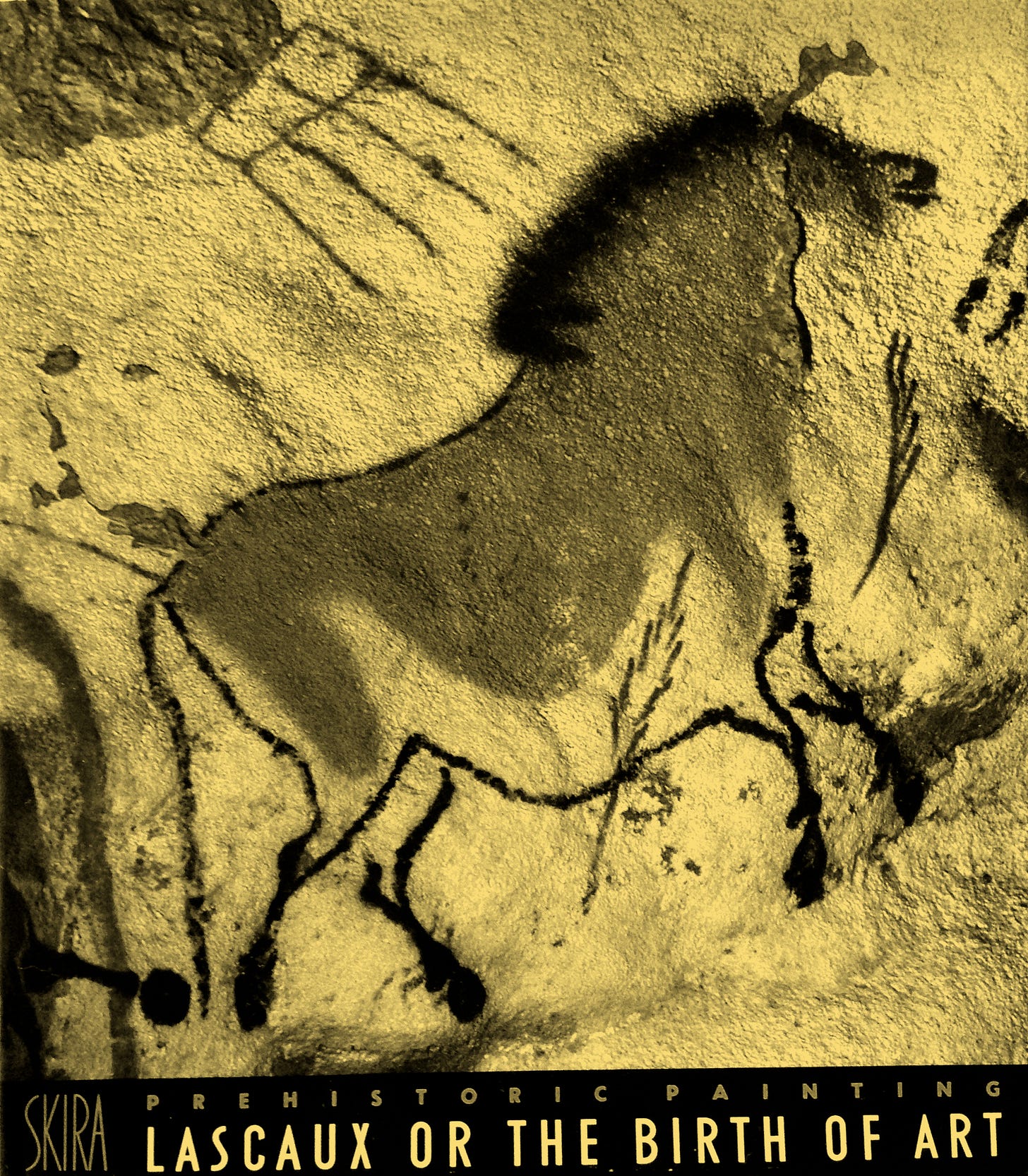

Georges Bataille’s 1955 volume on the Lascaux cave paintings. “The famous red hands we find in various caves, [Lacombe] said, that arch overhead, hand over hand stamped up a wall like rising heat... no one knew what these handprints were. Some now suspected they represented the Milky Way.”

The character who functions this way in Creation Lake is Bruno Lacombe, an old French radical who serves as mentor and inspiration to the members of Le Moulin, the anarchist commune that our narrator, “Sadie Smith,” has been hired to infiltrate.4 To be clear, Lacombe—unlike Reno—has real-life analogues: Kushner has copped to the character’s having begun life as a kind of mashup of Jacques Camatte (a ’68er who abandoned doctrinaire Communism for a primitivist existence in French cave country) and Jean-Michel Mension (a onetime member of Guy Debord’s pre-Situationist group the Lettrist International). But as Reno is to The Flamethrowers, Lacombe is the character around whom Creation Lake’s blended universe of real and fictional themes, its core philosophies and woolliest digressions, is arrayed. He is the book’s beating heart.5

In the present of the story, Lacombe is living in a cave in southwest France’s Guyenne region, a literal underground existence into which he’s been withdrawing for twelve years, the product of a gradual push toward anarcho-primitivist ideals that was accelerated by a personal tragedy: the death of his youngest daughter in a tractor accident. So OK, a fictional high concept, studded with politics and trauma—so far, so good. But of course, this being Kushner, we also do the “proximity to historical avant-garde fame” thing, and this time out, it’s a doozy: Lacombe was, we soon learn, an erstwhile Situationist back in the 1950s and ’60s, or at the very least a close associate of Guy Debord, whose long shadow and complicated theoretical/cultural/social mystique extends from Lacombe to Pascal Balmy, the leader of the Moulinards, who has styled himself in the image of the famous “filmmaker, writer, and provocateur.”

Guy Debord, his life and work and milieu—the 1950s Paris radical scene, the Situationist International, The Society of the Spectacle, May ’68 and its aftermath—is, even for Kushner, a big-ass subject. It’s here, in the book’s engagements with the S.I.-era revolutionary movement and its messy legacy, that the author’s skill for condensation, her almost gnomic clarity, really comes in for a workout. Debord was, we learn in a characteristically pithy one-liner, “moody and dickish,” a charismatic, notorious figure with “a legendary status that seemed to endure even now.”6 Most of what we hear about his theory and practice, meanwhile, is subordinated to his personality, his “cult magnetism,” and, especially, his gnarly alcoholism. We hear about Lacombe’s entry into Debord’s Left Bank demimonde, which was entirely predicated on stealing booze and robbing hotel rooms. We get reappraisals of the most mythic Debordian escapades and theories, unmasked by the authorial voice as rich kid compensatory gestures and hungover rationalizations:

Guy believed that true art never devolved into actual art, it had to be lived as a gesture, like going into Notre Dame Cathedral and yelling ‘God is dead,’ or stumbling home drunk, on foot, because there was a rail strike, and declaring that your drunken meandering was a new way of mapping the city.

The harshest critique is that of the end of Debord’s life, of the formerly suave revolutionary rendered a bitter, haggard, and—most indefensibly—spectacularized version of himself. “He hadn’t changed the world,” we read. “Instead, he had merely become famous.”

As in previous books, Kushner’s declarations have some of the queasy feel of coming right up to the edge of glibness, of biting off more than they can chew, of being fundamentally unearned. But at the risk of repeating myself: if you stop, think it over, or look into it, you realize that once again, the author is actually not wrong about any of this. The technique of the dérive, for one thing, did likely arise from an improvised response to a Paris metro strike.7 The end of Debord’s life does, in fact, seem to have been a sad spectacle (look it up). And—crucially—dude was a dick, at the very least, and nobody these days (who isn’t totally in the tank for what’s left of the S.I.’s legacy) would dispute it.8 Kushner pulls it off, in other words—this confident leveraging of realms of research to draw out these blunt, surprisingly bummer conclusions and connections within her semifictional world. But the bluntness, the confidence, the leveraging, it all has consequences. It results in her missing connections, too.

Take Burdmoore, one of the Moulinards to whom Sadie tries to cozy up, a wizened American veteran of the New York radical scene living out his old age on the French anarcho commune. Readers of The Flamethrowers will remember this dude as he first appeared in that novel, some forty years before these events, a young(er) 1970s revolutionary who’d logged time in his own notorious affinity group, the Motherfuckers. He was then and is now a clear analogue for Ben Morea, and when I saw him show up here, I got unreasonably psyched—not because he was a fun character whom I recognized, but because Morea himself had his own very notable overlaps with Debord, for whom he sort of auditioned to lead an American chapter of the Situationist International in the late 1960s. In the real world, it didn’t go well: the S.I. ended up detesting Morea and his “confusionist” group, Black Mask; they referred to his partner Allan Hoffman as a “mystical shithead” and literally wrote Morea a letter calling him a “cunt, piece of shit, liar.” And sure, they maybe Debord and his crew did this kind of thing a lot, but that doesn’t make it any less crazy, or the story possibilities it proffers any less exciting.

Indeed, if you’re as obsessed as I am with scene politics in the historical avant-garde, this shit is like dying and going to heaven. And even if you’re not, the reappearance of this character—and the connective potential he represents, for the mutually-reinforcing system of narrative richness that Kushner has built across two novels—is thrilling. It’s an opportunity to map two heretofore laggy nodes, to shade in characters who might otherwise read as stock types, to situate the Moulinards in a more complex relation with Debord’s legacy and with older waves of radicalism more generally. And yet, the Burdmoore of Creation Lake just kind of hangs out. He boasts and preens for Sadie, referring elliptically to his revolutionary past and joining her in a kind of mockery of the other environmental anarchists and ZAD castoffs that populate Le Moulin. But aside from figuring in some climactic plot action late in the book—a kind of inverted restaging of his real-world referent’s best-known claim to fame, the fact that Morea supposedly gave Valerie Solanas the gun she used on Warhol—we don’t dig any deeper on him.

Another bypassed opportunity shows up in what is perhaps the book’s essential thematic space: the caves of the subterranean Guyenne. This is the world from which Bruno Lacombe’s voice—his lengthy exploratory writings, which range from anti-civilizational invective to the transmigration of souls to Neanderthal cosmology—come to us (via Sadie, who has hacked the emails Lacombe sends when he’s aboveground and relates them to the reader across the length of the novel). Lacombe’s ruminations are the lushest sections of Creation Lake, the most beautiful and also the most revolutionary, charting his drift away from varieties of inherited, prefab insurrection and toward less dogmatic, more private ones: hollow earth reconceptions of history, the untold timespans before the ravages of mankind, the communion of generational voices along underground frequencies, cave paintings to star maps. This is a spirit, a messianism, a climactic eruption of the radical impulse that, everywhere else in the novel, appears as little more than banal gesture. At last—we’re made to understand—amid all the revolutionary posturing of the Moulinards and the Zadistes and the Debordians, here is a kind of truth.

But again, it’s more complicated than this split lets on. It is in fact a kind of truth, for example, that Debord practiced a rigorously earthbound politics and famously hated what he termed “mysticism” (thus the Black Mask takedown). And that’s without even getting into all the petty social scorekeeping and exclusionary polemicism and recurrent purges that characterized his style as Situationist leader—obviously, tendencies which are the furthest thing from spiritual. But that’s not to say that Debord never made lofty, borderline-eschatological projections.9

Or, even, that he never thought about caves. Indeed, amid the endless accounts of the jockeying and infighting that went on among the S.I. and its erstwhile allies, one of the most thoughtful and least sensational that I’ve encountered is in this Henri Lefebvre interview, conducted by Kristin Ross and published in a 1997 issue of October. Lefebvre, who ended up being on the receiving end of as much vitriol as any of the Situationists’ other eventual enemies, had also been good friends with Debord and his first wife, the great Michèle Bernstein. And though he fell out with the pair over what he refers to as “sordid reasons”—a true enough characterization that you can read about in the interview if you feel like it—he spends most of its length looking back on their collaboration at least somewhat magnanimously (moreso, anyway, than Debord deserved), including in his description of a group trip with the Situationists to the Pyrenees:

And we took a wonderful trip: we left Paris in a car and stopped at the Lascaux caves, which were closed not long after that. We were very taken up with the problem of the Lascaux caves. They are buried very deep, with even a well that was inaccessible—and all this was filled with paintings. How were these paintings made, who were they made for, since they weren't painted in order to be seen? The idea was that painting started as a critique.

This research, such as it is, seems to have come to naught; at least, I haven’t found any reference to Lascaux, or cave paintings more generally, in texts by Debord or crew. But I wasn’t surprised to know that these folks—whose obsessive interrogations into the uses and misuses of images coalesced across years of historical redefinition—would have been fascinated in what were then the earliest known examples of representational art in the West. Contemporary history would have played a role as well: the entrance to Lascaux was discovered in 1940 and the complex was opened to the public in 1948, putting the place and all its potential meaning on a collision course with all that postwar Euro theory could throw at it.

A snapshot of the discourse, its movement into the mainstream, and the wild cast of characters drawn out in the process, can be gained by tracking down Lascaux, or the Birth of Art, a 1955 monograph released as the leadoff cut in Skira’s “Great Centuries of Painting” series of coffee table books.10 The text, whose section headers have names like “Prohibition and Transgression” and “Man Achieves Awareness of Death, and Therewith Wraps It in Prohibitions,” was written by none other than Georges Bataille, whom Albert Skira credits in the intro with the idea for the book. Although this crossover is a particularly fun one—what other thinker could have been counted on to juice the Guyenne cavern system’s megafauna depictions into “the game of birth and death played on stone”?—again, it’s not that surprising; as Kushner demonstrates in Lacombe’s sections of Creation Lake, the “problem of the caves” is a topic which, for three quarters of a century now, has yielded infinite rewards for those of a certain cast of mind. Lacombe, Lefebvre, Debord, Bataille: obviously, Lascaux exerts a pull on theoreticians. But how could it not? Caves attract cavemen.

I took this photo on December 30, 2024, during a visit to Los Angeles. “In my reassessments, [Lacombe] said, I have lost my bearings, and I will have to find new ones. With that, he signed off.”

Phew OK—almost done, I swear, but first, some questions which can’t be ducked. What, for starters, am I asking of Creation Lake? In pointing out the trivia that the author “missed,” am I suggesting some specific alternative, some balance between the yields of research and the exigencies of narrative that Kushner ought to have struck but didn’t? If not, then why bring all this shit up?

In fact, it’s particularly hard to fault Creation Lake its various liberties, the summary view it sometimes takes with regard to the intricate radical histories it approaches, and not just because those histories are immensely arcane, even for a writer as down as Kushner obviously is.11 Rather, it’s because Kushner’s method, as I tried to outline it above, is itself tremendously complex, and because the way it ingests and reemploys facts and connections tends, again, to yield results no less “true” for their having been boiled down or selectively snapped up. Giddle’s rationalizations; Reno’s surrender; Lacombe’s mystical conversion; Debord’s sleaziness; these character turns are possessed of an undeniable authenticity, and they’re all furnished by contextual support, real-world correspondences that are deftly handled to a one.

In puzzling out the missing connections that I’d expected or hoped to see, my point is not to complicate the book’s construction for its own sake, much less to try and spring a bunch of historical gotchas or whatever (and, honestly, I’d be surprised if Kushner wasn’t already aware of, say, the one-sided feud between Debord and Ben Morea, or even the story of the Situationists having visited Lascaux). The point is to be aware of what’s been selected and what’s been elided, these choices that Kushner has made, and to understand the ways in which those choices accumulate and put themselves to use, weakening some readings of the book even as they reinforce others. And from that perspective—with an eye on where this kind of larger thematic weight goes—it becomes clear that what is being reinforced in Creation Lake is, most of all, a decidedly dubious vision of the revolutionary left.

The most obvious example of this is in the book’s sustained characterization of Le Moulin as a cheapened, clumsy pantomime of a committed anarchist commune: a community rife with unspoken scandal, fundamentally retrograde in matters of sex and gender, and subject to an imperial cult around its leader, Pascal Balmy, who turns out to be, at best, a real sucker. And actually, it’s not just the Moulinards; this sort of impoverished depiction eventually colors everyone connected to the movement.12 Contemporary anarchism ends up being treated like nothing so much as a factory for patsies, so much so that when the actual plot climax—Sadie’s effort to entrap the Moulinards into the murder of a government official—arrives, the fact that the whole plan falls apart spectacularly, like something out of The Third Generation, feels less like a condemnation of a political calculus than a promise, repeated at length across the entire novel, on which the author has merely followed through.

The real tragedy, the real failure of radical potential, appears not in the book’s more or less satirical portrayal of the Moulinards, or indeed of any of the many dopes in their orbit (including, for some reason that eluded me, an obvious analogue of Michel Houellebecq—the inclusion of whom might be a cool act of authorial score-settling or might be, as I felt, a weird distracting detail, destined to unnecessarily date this book). The book’s true forfeit of revolutionary possibility is an altogether quieter one, but it arrives via the character to whom, in stark contrast to the bungling Moulinards, the book’s moral high ground has been ceded: Bruno Lacombe.

Late in Creation Lake, there’s an account of an email from Lacombe describing his theoretical divergence from another of the Moulinards’ mentors, a character named Jean Violaine—a fellow traveler from the ’68 era, but one for whom the revolution is still alive, albeit on the level of local, small-scale organization; market protections for peasants, collective bargaining, that kind of thing. “Trying to dismantle capitalism from within capitalism is a dead end,” Lacombe writes, criticizing the Moulinards for taking up with Violaine and in the process voicing a version of the kind of “reformism vs. insurrection” question that has animated generations of debate on the left. “You fight for a lost status quo… and your victory is what? A slightly more functional capitalist relation. That’s all.”

Except that the revolution Lacombe proposes—his counter-offer to the path of steady, piddling reforms wrested from the state via thankless struggle—is no revolution at all. In keeping with the character’s inward spiritual tilt, the Lacombian equivalent of insurrectionary action is a deep internal examination, an abstract effort drawing on the accumulated messianic potential he’s encountered down in the caves, amid Bataille’s “game of birth and death played on stone”:

But, [Lacombe] said, I understand that Jean’s way, the tireless organizing, the debates, the little victories, is more straightforward than what I might propose, than what might constitute “my way.” Plumbing the depths inside yourself is not easy work. It is difficult work. But I am convinced, he said, that the way to break free of what we are is to find out who we might have been, and to try to restore some kernel of our lost essence.

Like much of what Lacombe has to tell us, the sentiment is as striking as it is true, formed powerfully and convincingly from the web of connective contexts out of which Kushner has fashioned the character. Lacombe’s history, as an orphan regurgitated out of the maw of the Second World War into Parisian reformitories and jail cells, the years as Debord’s running buddy and the subsequent failure of the ’68er movement, the loss of his daughter and the descent into the caves: we feel it all in his tone of warning, in his quiet insistence.

That Lacombe’s proposal denotes a downshift in revolutionary possibility—a reduction in expectations, a retreat from the fullness of the world that can reasonably be attained, even in the space of imagination—doesn’t feel like an accident, though it certainly comes off mournful. It may be exactly what Kushner intends us to understand, at least in part. It wouldn’t be the first time, after all, that the author has dealt in such bummers.

______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______

| |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| |

| () || () || () || () || () || () || () || () || () |

|______||______||______||______||______||______||______||______||______|

______ ___ __ __ ____ ___ ___ ____ ____ ____ ____ ______

| |__| | / __)( )( )( _ \/ __) / __)( _ \(_ _)( _ \( ___) | |__| |

| () | \__ \ )(__)( ) _ <\__ \( (__ ) / _)(_ ) _ < )__) | () |

|______| (___/(______)(____/(___/ \___)(_)\_)(____)(____/(____) |______|

______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______

| |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| || |__| |

| () || () || () || () || () || () || () || () || () |

|______||______||______||______||______||______||______||______||______|Luckily things are back on track here in 2025, as can be plainly seen in the video everyone sent me of the stray dog that was first to cross the newly-opened Romanian border, Spy Who Came in from the Cold–style.

Not to mention its late-inning launch into the Italian protest movement, which maybe necessarily feels somewhat more borrowed than the stuff set in the US. For instance, Kushner did, literally, steal the ending of the book from Nanni Balestrini, as she describes in her introduction to the Verso edition of We Want Everything.

Also, such a sick character name. Giddle!

Speaking of names, real and fake: impossible to write this post without acknowledging the fact that I’ve got an actual friend actually named Sadie Smith. Not a cryptonym. Sorry, Sadie, for all the scare quotes.

It’s also notable (and cool, IMO) that this is pointedly not the case for Sadie, the book’s narrator and nominal protagonist, about whom we know very little.

Worth noting: the caustic descriptions of Debord come to us through the first-person narration of Sadie, who (for most of the book anyway) is a literal spy who actively means to harm the movement she’s describing.

At least, that’s what’s suggested in Jean-Michel Mension’s tea-spilling memoir The Tribe, which is definitely where Kushner got almost all of the details on Debord that are related in Creation Lake.

The book also includes a character who briefly surfaces the fact that Debord is now known to have had—at the very least—a sexual relationship with his sister Michèle Labaste, a truth that seems to have came to light in a controversial 2015 biography and whose implications have been litigated in competing texts ever since. Similar to Sadie, though, the character in Creation Lake who brings this up is an outlier among the Moulinards, someone who’s got reasons for decrying the group’s fealty to Debord. Which is to say that, while I can make an educated guess as to how Kushner herself feels about the man, the built-in narrative distance is such that we come away from her book not knowing for sure.

From Comments on the Society of the Spectacle (1988):

We must conclude that a changeover is imminent and ineluctable in the co-opted cast who serve the interests of domination, and above all manage the protection of that domination. In such an affair, innovation will surely not be displayed on the spectacle’s stage. It appears instead like lightning, which we know only when it strikes. This changeover, which will conclude decisively the work of these spectacular times, will occur discreetly, and conspiratorially, even though it concerns those within the inner circles of power. It will select those who will share the central exigency that they clearly see what obstacles they have overcome, and of what they are capable.

My Romanian grandfather, who made the pursuit of classical erudition a kind of lifelong centerpiece of his persona, proudly displayed the full set of Skira monographs on his shelf. I’ve since inherited the books, and also gotten a tattoo of the Lascaux volume’s cover, thereby ensuring that I won’t be beating the “pompous blowhard” allegations either.

Maybe here’s a good place to note that I myself have so, so much to learn about Situationist theory, its history, and its legacy. I’m really wary of seeming to lecture when, in spite of having been psyched on these guys and studied them on and off for years, part of me is certain I don’t know what I’m talking about.

One of whom—the female half of a pair of ZAD veterans who show up at Le Moulin to get duped by Sadie—gets the nickname of “Mao II,” an almost Pynchonian exercise on Kushner’s part in terms of lengths gone to for the sake of a dumb joke. Respect to Rachel K.; it’s so worth it.

This is a great and, honestly, fun read. I echo a lot of the same sentiments, loving Kusher and being somewhat let down by the novel in some respects, but I think you make such a strong argument for the overall Kusher project. Thanks for writing this.

Great essay! I have a copy of The Flamethrowers I got in a Little Free Library but haven't got around to it, but this inspired me to pick it up.

I am curious, in what way do you mean the reference to Houellebecq could date the book?