TRANSLATION // jean-louis costes

“the only true heroics come from those who make no excuses for the indulgences endemic to a society that imagines itself civilized while hiding its true face.”

I have always been a colossal poseur, but possibly never more so than when, in 2010--as a twenty-one-year-old noiseboy with like two years of French class under my belt--I and my friends decided to write to Jean-Louis Costes. Banking hard on our precociousness to cover for multiple levels of cultural and linguistic stolen valor, we tried to come off as old hands in the underground, pitched an interview for our zine, and proclaimed our admiration via statements like “j'appreciais beaucoup votre shit-flinging style.”

Costes, however, turned out to be really chill, and agreed to the interview straight away. He also encouraged us to translate his novella Viva la merda, which I went on to do, not that well, later that year. Although we talked about publishing schemes on and off, neither of us had any prospects in the English-language book game, let alone any money to do the thing ourselves, so the translation never came out--a fact which, looking back, I’m completely cool with. The project did, however, teach me a lot about translation and idiomatic French, and it constituted my first but by no means last encounter with the word “pétomane.”

Below, I’ve included the text of our interview, conducted via email in March 2010, followed by the wildly pompous «Non-Preface» I wrote for my Viva la merda translation, the text of which pilfers freely from the interview. The actual novella translation, meanwhile, is still far too nasty to post.

OK happy Thanksgiving!!

Costes being interviewed on Tout le monde en parle in 2006 (video), in which he considers the difference between an “artiste de merde” and a “merde-artiste.”

What do you call your art?

I don’t have a special name for the songs, but they might be called “pop noise.” My shows, I call “porno-social operas.” Operas that treat their personal or social subjects with the brutality and crudeness of porno.

How did you begin to play music?

I began by playing keyboard and guitar in a hard rock group on the weekends when I was a student. But, since I’m asocial and played bizarrely, the other musicians didn’t like me. And, around 1985, I ended up playing alone, producing everything myself in a home studio. Very quickly, free of the censorship exerted by the other musicians, my music evolved into a blend of pop melodies and noise. Then, on stage, it took the form of opera little by little.

Who are the artists working today whom you admire?

I’m totally engulfed in my own work and don’t know much of contemporary art. My only true cultural references go back to childhood: Tintin comics and Disney animation. For work of the present, I’m my own influence. I create by reacting to my prior work. For example, a violent noisy song after a sweet melody. And I also create by reacting to events in my private life, and from the most dramatic news that’s pushed by the media.

You’ve done a lot of your work with collaborators. What new elements do they bring?

Most of my music is created alone. Sometimes I use music made by other musicians, but I finalize the arrangements myself, the voices and the mix, because I have trouble working in the presence of other people.

My principal collaboration is with the actors in my shows. I bring the story and the music, but we define the interpretation together during rehearsals.

Occasionally, I meet people with whom I fully collaborate. For example, during the ’90s, the collaboration with Lisa Carver Suckdog, on the first operas, was total. We truly conceived of everything together. At the moment, I have a collaborative project of the same intensity with DJ Sebastian, whose music I admire, the effective clarity of the style, the power of the work: he’s currently producing some songs based on fragments I’ve proposed to him, and I hope it’ll lead very quickly to a release and some concerts.

What’s the goal of your art? Of art in general?

I don’t know why I make art. It’s a mystery. A strange force pushes me to do it, as if I’m being directed by an external spirit. In any case, I’m not looking to spread any social, philosophical, or aesthetic message. I create instinctively. I manipulate sound, but ultimately it’s always the sound that decides where to go.

What role does writing play in your practice?

Writing isn’t sensual like music, but it taps deeper into the mind. Our beliefs are ultimately nothing but an assemblage of words. If I play with these assemblages, it’s like manipulating bombs. There’s no such thing as an assemblage of sacrilegious sounds, but there is such thing as an assemblage of sacrilegious words. You can’t be assassinated for a melody, but you can be assassinated for your words. To make art with words is to risk one’s life.

You’ve worked around the world. Are there difference between audiences in Europe and audiences in America or Asia, with regard to your reception?

Even in the same city there are differences between audiences from one day to the next, one place to the other. It’s pretty unpredictable. But, generally speaking, European audiences react more mentally, American audiences more physically, Asian audiences... with smiles! But that’s just sticking to generalities, because obviously each spectator interprets my work in their own way. Because, since I don’t offer any message in my work, each finds whatever they seek.

Are there differences between the public of today and of the old days?

Back then the concert would be interrupted after five minutes by a deluge of beer bottles thrown onstage. Nowadays, I don’t get more than two beer bottles per show. And, back then, the overall audience was male; my songs were considered too brutal for girls. Today, the majority of my fans are girls who find the same songs romantic. The ugliness of old has become the beauty of the present!

Is there such thing as ‘too much’ in art?

For me there’s no ‘too much,’ because art is the only possible place to symbolically express evil. An art that never represents what’s forbidden is dishonest. For me, the only ‘too much’ would be to die for my work. To die accidentally because of a poorly planned performance, or to die assassinated by an anti-art zealot. Although to die on stage may be my great secret fantasy!

What are your thoughts on noise in the museums?

Contemporary institutional art, which is a machine for killing true art, encourages false art that expresses no human passions. Like abstract art, pure noise has nothing to say, and is thus perfectly acceptable in museums. Those who are true artists, unpredictable expressionists, won’t be accepted into museums until after their death.

In the United States, we encounter the French avant-garde tradition in a very specific context. How does one encounter it in France? Do all French students know Breton and Bataille? Céline and Guyotat? Are they still essential? Were they ever essential?

Everyone, in the cutting-edge creative milieu, knows these artists. For me, Céline and Guyotat are models of artistic integrity, seuls contre tous, who went the deepest into themselves, and thus into us. As for Breton, his dogmatic side, drafting aesthetic manifestos, makes me feel more distant from him.

It seems that the end of the world is close. Are we wrong?

It’s possible that the end of humanity may be close. But the cockroaches and spiders will remain. World War III will be between the cockroaches and the spiders.

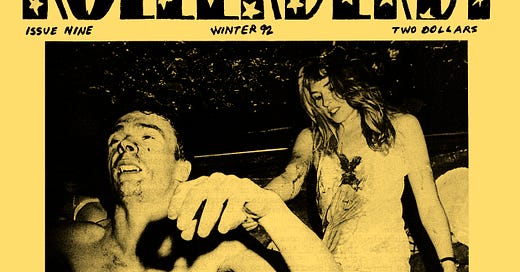

Costes with Dame Darcy on the cover of Rollerderby #9.

Viva la merda! (Long live shit!), a film from the mind of Costes

NON-PREFACE1

Pop melodies spiked with harsh noise blasts. Porno-social opera. Tintin and Disney. Close-up on sacrilege committed openly and with pride, as we zoom out to take in the shabby plastic furniture, microwave dinners, TV guides. A voiceover screaming bloody murder, raving against the wash of violence and corruption, reaching in desperation toward some sort of sanctuary, a glint of ocean sun and freedom, a final transcendence beneath the waves as the end credits roll. Like Céline, like Guyotat, seuls contre tous, resistance to all dogma steadfast and assured, the path to glory a necessarily solitary one. The ultimate desire that underlies such diametric individual opposition to a society of bland uniformity remains denunciation, vilification, perhaps assassination by some anti-art zealot—how else to define a positive outcome to the path of total resistance? Our heroes are doomed, and it is we who have doomed them.

Such are some extreme parameters of the doctrine espoused in the following pages. Developed and honed through endless, wanton, and often cruel confrontation—with pop culture tropes, with staid readers’ stale expectations, with mores of class, race, gender—the endgame here is permanent reconfiguration of the senses. Long live shit, which, in these pages transfigured magically, can (and will) stand in for anything: body and blood, soul and divinity, ‘til the whole thing glints positively liturgically. Though Costes’s writing has never before appeared in English, his music and performances are recalled in the United States with knowing smiles, sidelong glances, and telling shifts of eyebrow, and readers will no doubt come to find some analogous expression settle, before too long, over their unaccustomed features.

The policemen enter and the priest points them out.

“Here are the lost sheep.”

The officer examines them closely. With the tip of a fingernail, he scrapes a speck of shit from the girl’s cheek and has a taste...

“It’s the real thing! Book ’em!”

Two policemen place the dazed couple in handcuffs and force them outside.

“God bless you, my children!” calls the priest, pushing the church door shut.

Meanwhile, Costes’s limitless assault is not incommensurate with the cruelty of his targets. Think what you want about the work or its author, but it’s quite obvious that if we’re going to get anywhere, we will need voices similarly given to excess and abandon. The world will end, soon, or dread will propagate before us while we grow old, until we’re left to watch our grandchildren sweat it out. Either way we are going nowhere fast and one need only check the papers for confirmation. In Costes’s twenty-first century—in which his song “Kakakamikaze” seems to always be on the radio—of course, this dérapage is brought to its logical conclusion: politics is theater, fascism is rampant, media hypocrisy strangles free thought, and the only true heroics come from those who make no excuses for the indulgences endemic to a society that imagines itself civilized while hiding its true face. Parents, priests, police, politicians, landlords, doctors: all harbor a secret scatological fascination. The newsmedia trumpets violence but cravenly covers up any reference to perversion. What allows our heroes to stand out from this gaggle of hypocrites? Namely, the honesty and openness with which they indulge in transgressive exploration. Wearing their messianic trust openly on their bodies, their only enemies are doubt and shame, imposed from without, boiling up from within. Their eventual freedom lies in total commitment, realized at length and effort, to the apocalypse they engender. We should all be so lucky.

No comment.

█████ ████████

░░███ ░░░░░███

██████████ ███░███████ █████ ██████ ████████ ████░███████ ██████

███░░░░███ ░███░███░░██████░░ ███░░██░░███░░██░░███░███░░██████░░███

░░█████░███ ░███░███ ░██░░█████░███ ░░░ ░███ ░░░ ░███░███ ░██░███████

░░░░██░███ ░███░███ ░███░░░░██░███ ███░███ ░███░███ ░██░███░░░

██████░░███████████████ ██████░░██████ █████ ████████████░░██████

░░░░░░ ░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░ ░░░░░░ ░░░░░░ ░░░░░ ░░░░░░░░░░░░ ░░░░░░ Even as a kid, I was abundantly aware that doing this project was kind of a weird career move, so I originally signed this piece—as well as the translation as a whole—under a fake name so stupid that I will never reveal it to anybody.