INTERVIEW // MSHR

“The only practical approach was total, radical collaboration.”

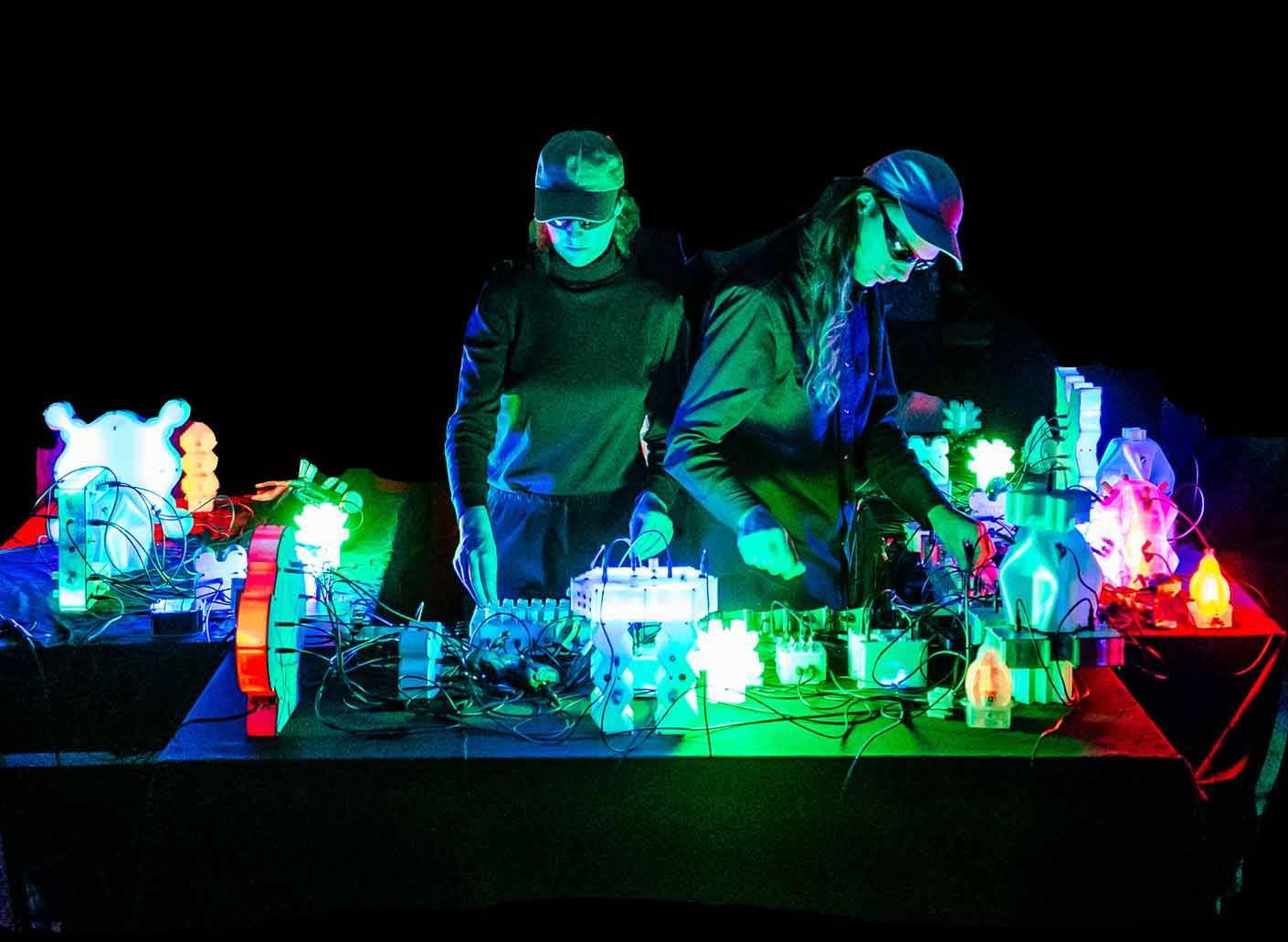

This week, it’s a good one: a lengthy-but-lively, heady-but-loose conversation with MSHR, the long-running art collective/performance and installation project/killer electronic music outfit founded and embodied by Brenna Murphy and Birch Cooper.

I met Brenna and Birch in the summer of 2011--I was on tour, it was my first time in Portland, and friends of friends had suggested we rendezvous at the studio of a couple of artists whose work was said to comprise some blend of the madcap cross-genre multimedia art tradition with the dedicatedly DIY spirit of the noise scene. Incomplete info, obviously, but enough for me to get very psyched and become fast friends with the pair, and when I later saw MSHR perform--a live spectacle of sensory deluge via homemade synthesizers and sound-light interaction--I was locked in for good.

Over the ensuing years, I’ve been lucky enough to hang with MSHR across numerous zones (scope their spring 2025 itinerary for proof of uncommon touring prowess), see them play a ton (here’s them crushing it at last month’s iteration of Artists Space’s Abasement series), and participate in collaborations including a monograph, video art piece, and book launch performance. And, since Brenna and Birch spent a chunk of this summer here in NYC, it didn’t take long for us to get to talking about a possible interview.

Below, find the result: a chat about Pacific Northwest DIY, generative systems, the wack ideologies behind corporate tech, and non-narrative multidimensionality, conducted at a Tibetan spot near MSHR’s Jackson Heights sublet on what was probably the hottest day of the year--a fact which may have had some bearing on the baseline revulsion evidenced in our AI takes. You decide.

The first thing is just that in preparing for this, I realized that I didn’t know how you guys started making stuff. What were the, like, formative experiences that led you toward this project?

Brenna: Individually? Or how we started with MSHR?

Everything.

Birch: One way of telling this is to start very far back, which might take a long time.

Brenna: Or another way is to start when we start working together.

Birch: Yeah, let’s start there, and then we can go forward and backwards from that point. We both moved to Portland. And I was able, with some friends, to find a house in an area that later became a kind of ground zero for Portland gentrification, of course, which is to say that we would never be able to rent a house in this area again. This kind of hippie with an inheritance had bought this old building and painted it beautiful colors.

Brenna: A Victorian house. Like, a hundred years old, with red, yellow—

Birch: Like a sunset gradient.

Brenna: And with a kiwi plant that went over the entrance. Like, really magical.

Birch: So, we immediately knew this was the spot and this woman took pity on us and rented us the house. And then Brenna moved in shortly after.

Brenna: So we met because we moved into the same house together.

When was that?

Brenna: 2007. And then everyone in the house started an art collective together. And we worked really intensely together for four years in that group, in that house. And when that disbanded and we all moved out, then Birch and I started working together as a duo.

Birch: But that group was enough people, especially at the beginning, that it just couldn’t not be really prismatic in terms of the kind of work we were making. It was kind of everything at once: a band, but also building instruments, also doing installations, costumes, performance art, video art, sculpture, just all of that constantly recombined. But there was a big emphasis on installation and performance. And in the installations, we would usually have interactive sound-light systems.

Brenna: And it was also really world-building; we were always coming up with characters and stories and worlds and costumes. Our installations were sort of environments for these worlds. And our performances were like rituals or, like, re-enactments of things happening in those worlds.

Birch: Yeah. It was very Pacific Northwest; we were all from the Pacific Northwest. And it emerged out of Pacific Northwest DIY music culture, in a way. But we had all studied art and music, and we were very into experimental music—and, really, electronic music.

(Lots) more live videos here.

OK, yeah, it’s telling that you would have functioned as a band and as an art collective--or a single artist, in a way--and that these different identities, as well as these different sorts of time and space scales, were being constantly called up. Important because of how it seems to describe your work as MSHR now, but also because this kind of totally open practice--where you’re exploring all these forms, and doing it in experimental spaces but also gallery spaces--all this kind of stuff comes out of DIY, it seems to me. Or at least, more that than, like, being a more traditional artist who then gets excited about other forms or other media or whatever.

Birch: Totally. Yeah, we were all really from underground music culture in Portland, Olympia and Seattle. The noise scene was very good at that point, which is what we were mainly engaged with.

Brenna: There was a pretty good underground art scene too. People had, like, galleries in their garages, and were really open to interdisciplinary projects.

Birch: I think we were all kind of captivated by the idea of a collective. Like on the east coast, of course, there were some shining examples of art collectives that were a little bit older than us, that we were really excited about. And there were also groups like Ant Farm, and older examples like that, which were really interesting.

Who were some of the east coast guys?

Birch: Forcefield, Paper Rad, groups like that, they were just really exciting. I’d never been to the eastern seaboard, and wouldn’t go for years, but it had all drifted over through people touring, basically. Or, like, people moving from Boston to Portland.

Brenna: And I think an important part of our lineage story in that group is that one of the members, Jason Traeger, was older and he’d had a pretty amazing history through all these different underground scenes up and down the west coast: like, he’d been part of the hardcore scene in San Diego in the ‘80s, roadied for 7 Seconds as a teenager, then he worked at Alternative Tentacles for Jello Biafra in San Francisco, then lived in Olympia in the ‘90s and was involved in the K Records scene. Then he moved to Portland and went to art school, and that’s when we all met. So he really brought a lot to the group.

Birch: Yeah, he was the much wiser, high functioning one. He was also the one who came up with the name for the collective, Oregon Painting Society. Which was meant as a joke about an imaginary, conservative hobbyist group of older painters. Jason was the only one of us who really was, and still is, a painter.

Those group dynamics are always interesting: there’s a certain amount of intention, obviously, when you like create something, but there’s also just like the fact of the players involved and like the parameters that got set up, sometimes on accident, that determine its course.

Birch: It’s all about emergence, which is still such a central idea in our work now. And I don’t think I was quite able to articulate this at the time, but that’s the point of a collective]—that third mind that emerges. Or however many people, you know. If it’s a good collaboration, you get something that goes beyond the participants.

Brenna: It was really important, in Oregon Painting Society, that elements of the project weren’t attributed to the different people. It was always collective authorship.

Birch: Yeah. And when we got kind of like boiled down to what became the, I guess, the final crew, the people who really stayed… that was still, like, five people. Which is a lot of people to have a conversation with about what an installation should be, you know?

Yeah, and in the context of your work now, none of this is, like I said, particularly shocking--this idea of working in a collective where the individual identities are kind of subsumed into it. I mean, you both have individual practices as well, but when it’s MSHR, it feels like it’s the unit that’s central.

Birch: Right. We really took those lessons to heart. In Oregon Painting Society, there were many times where people would delete someone else’s work, or change what someone else had done, or use part of it in a different way… The only practical approach was total, radical collaboration.

And you mentioned “emergence” as a central theme.

Birch: Oh yeah. Well, I mean, anyone who’s done a band has had that experience, you know? Where, like, if it’s a good band, that probably means that the shared world has grown really big. Even the impulse to make our own instruments, that’s the same thing: it’s the recognition of the tool as a collaborator, and the desire to be surprised by your collaborator, or to have something outside of yourself be the outcome of your work. That interaction, with a tool that exhibits behavior of its own, that’s the same idea. Or, you know, our interest in generative systems, obviously, is an interest in emergence. All these ideas kind of triangulate on that.

The idea of these kinds of constraints and parameters being built up into generative systems feels so intrinsic to the history of experimental art, though certainly not only experimental art. The way that that sort of lineage manifests in real, functioning technologies can be really interesting, and obviously, it’s something that so many people are sort of getting obsessed with now, whether as artists or just as consumers. But you guys have what can sometimes feel like an uncommonly rigorous approach to technology: you build your own gear, you use open-source software, etc.

Brenna: Yeah, of course. We’re very critical of using corporate tech in general and especially in our work. Because, obviously, they don’t have the best intentions, and if you’re going to use those tools you’re taking on whatever biases or mentalities went into developing them. Especially when you’re talking about “generative art” that’s created with consumer AI. I mean, it just seems to me that whatever you make in there is gonna be shaped by algorithms developed in service to the most absolutely wack ideologies and motives. So it’s sort of like, not the emergence we’re looking for.

One of MSHR’s handbuilt synths.

Birch: Right. Of course generative systems aren’t intrinsically good, right? I mean, our culture treats capitalism as a generative system—it could be the basis for an interesting sound piece, but as a global economic system it’s very destructive. And additionally, like, consumer culture is repulsive, and the exact opposite of what we’re trying to do in our work. So in a lot of ways we position ourselves in opposition to all of that. It seems like kind of a ’90s thing, in a way. But also, just the idea that when you make a tool, that’s a way of composing. The tool is the composition in our work, or at least a part of the composition that is added to other parts to make the whole. And so I take a kind of extreme view, which is that if I were playing an instrument designed by someone else, I would be performing someone else’s music. Of course, we live in a culture built on countless generations of human technology, so we’re choosing arbitrary levels of technology to punch in at in our practice, but trying to be intentional about where we punch in.

Yeah, I think there’s something to that. And while that’s a relevant consideration for any artist making work with any kind of tool—which is everyone—I think it’s probably all the more relevant when the technology or tool you’re using bears some greater perceived resemblance to these consumer technologies that have become really dominant in our world.

Like, for instance, lately I’ve been really interested in thinking about and writing about VR art. And when I first started reading about it, I was struck--though I probably shouldn’t have been--by how many of the early exhibitions and funding opportunities and institutional thinktanks were sponsored by Intel, or governments, or whatever, obviously as a means of gaining a kind of soft power for the technology through the use of art. Some of the pieces produced under these kinds of conditions were really cool, and really critical, but still, it’s obvious--and again, this is news to no one--that by accommodating yourself to that arrangement, even if you’re using it to be critical, you’re still locking yourself into a compromised, exploitative dynamic. Or maybe, less dramatically: any art that really overtly uses some new technology that has a consumer dimension necessarily becomes a commercial for that technology.

Birch: Yeah, we’re interfacing with this question all the time.

Brenna: Just last week, an organization that we like asked us if we’d want to participate in a panel about AI and art—but, like, the event is funded by a big AI company. And we were like, well, we don’t use AI at all, ever, for anything. We’re really critical of its use in the arts and other fields. But maybe we could participate in this panel and be a critical voice. But I don’t know. It would still be participating in this kind of hype event that’s basically functioning as a sort of commercial for this big tech company.

There is definitely a viable slot for a voice like that, and to be clear, I don’t think that the complexity of this kind of participation is enough to justify not participating, or never participating, if that were even possible. But meanwhile--to get kinda paranoid about it--the institutions know that that’s the bind, and they allow for that, and they will make a space for those kinds of participation, this kind of inclusion of critical voices, in order to maintain their broader dominance.

Birch: Well, it’s interesting, there’s such a history, such a tradition of new tech being just immediately absorbed by artists. Like E.A.T. and the “9 Evenings” series with Bell Labs, which has always been such a big touchstone for us, as something that we just adored. But recently—like, in light of this recent event—we’ve been rethinking it.

Brenna: Like, why does this contemporary situation rub me so wrong, when I see the historic E.A.T./Bell Labs collab as so cool? Were there artists at the time that were critical of collaborating with Bell Labs? Was Bell less sinister than the tech companies nowadays?

I think it does feel the same, and it also feels useful as an example. Like, obviously, there are these canonical stories that everyone cites: everybody talks about the New York Abstract Expressionists being funded by the CIA, stuff like that. There are numerous obvious cases of these kinds of arrangements that then yield work that may or may not be central to someone’s worldview, or important on the level of artistic development, or just meaningful to you or me. I think the unavoidable reality is that we’re all aligning with and breaking with various institutions all the time, and the real work is maybe, one, to recognize that, and two, just to manage that complexity in a thoughtful and principled way. I am really interested in thinking about what a calculus might look like, of when to do that and when not, or how and how not, and what the possible ethics might be. But meanwhile, while that work has to do with uncovering these more hidden structures, there are also plenty of cases where it’s not at all hidden, and you see the deal clearly and it skeeves you out. And in those cases, I totally understand being like, “Fuck no, I won’t participate.”

Birch: Yeah. I just turned 40 and Brenna’s 39, so we’ve been through a few waves of new technology and seen how they were processed culturally in the arts. When it was happening in our twenties, I think I was more caught up in it, maybe. Like: there’s something new happening, it’s very exciting, artists are all rushing to use the new technology, and the art world is sort of falling all over itself to make art shows about this new idea. But the cycle has repeated enough times in our lives by now that the pattern is wearing a groove.

Like there’s no content, it’s just a behavior.

Birch: Yeah, yeah. We’re kind of hyperfocusing on this, but I think it does feel like it has a kind of monad of relevance in our conversation. Because yeah, we’re trying to use open-source software and/or build our own tools. And as a result, our work often seems, like, retro to people. I think that’s interesting.

That is interesting. As if it necessarily has to be referring to some previous era when people were... what, less dominated by top-down systems?

Still, that does make me think of some of the very specific qualities in your work, and how they might follow from these principles and these parameters. Like, obviously your setups, your tools, are generative in the strict technological sense or whatever, but they’re also generative in the sense of being reflexive and recursive: they illustrate the system even as they are operated by it, and then that reflexive gesture generates another dimension, another layer of illustration and another layer of operation. I don’t know if that makes any sense.

Maybe this is a good illustration: like, I know that you guys design some of your gear in shapes that are visualizations, like diagrams and schematics, of some part of the system. And so they’re functional as diagrams, but then they’re also sculptural and distinct artworks. They’re these little guys, you know, but they contain this other dimension too, as symbols or sigils or runes, and the performance then entangles those meanings and makes it impossible to tell where one ends and the other begins. That’s a kind of generative quality that pulls from all of these levels at once. I don’t know what my question is, exactly; maybe I just want to know how you think about the interaction of these kinds of sculptural elements with the sonic ones.

Birch: Like, what relationship or role do these things have in our work? I think one answer is that digital sculpture and electronic sound were initially separate nodes in our work that just intuitively seemed to have a lot in common. And then we’ve just been spinning that around in our minds and in our practice. Because there’s not really a linear correlation between the two, it creates this generative sort of imbalance that just, like, keeps spinning. They inspire each other a lot.

Yeah. I can think of somewhat simpler examples in your work, too. Like Birch, I remember seeing works of yours that were, like, digital sculptures on a photographic background. Or Brenna, like your work in print. Your Floating World newspaper, or the Pleasure Editions book we did. This idea of just, like, troubling the format in this way or something. But, you know, you can do that and have that be the entire point of it, but in these cases, it’s not. It’s like a first step, if anything.

Brenna: Yeah I guess when we’re working with one medium, or one dimension, we always want it to bleed into the next one. And when you map one thing onto another thing, you can sometimes see something about it that you might not have seen before. So pushing things through these different dimensions can kind of reveal some inherent shape that’s there, or some other angle to that shape.

Video documentation of Field Transducer Circuit, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, 2023.

And what about virtual worlds, and spaces, and “play,” in, like, the art-theory sense or whatever? Like, I’ve played several game-type things that you guys have made. Is there something about creating a world that feels like a logical expansion of this idea?

Birch: Totally.

Brenna: I really like organizing space, as a medium in itself—like a spatial composition to be experienced from the inside, or as a participant, sometimes virtual, sometimes physical, sometimes both. We’re really designing an environment that’s meant to be experienced through spatial exploration.

Birch: Or that spatial exploration is somehow the way that a composition unfolds. Sometimes in a really literal way, like just exploring a room or sometimes in a less linear way, where exploration acts as an input to trigger mutation in a piece.

Brenna: Did you see our VR installation?

At PS1? Yeah.

Brenna: That’s kind of like what you were talking about, with the diagrams being the map of the space as you move. And for us to use VR, it was really important to use it spatially, so that you weren’t just sitting there and looking around, but like really moving your body throughout the room.

Birch: Yeah. There were a lot of recursive sort of loops in that piece, like using the system diagram as the kind of architecture of both the virtual and physical space, which visitors navigated to interact with the system. But yeah, neither of us were or are video game heads. We’re both installation artists. And so those technologies always reflected our installation practice. But also working between a lot of mediums, I think, kind of leads to “worlding,” in a sense, because I think we kind of intuitively just want to make work that combines dimensions, and then that becomes kind of a cohesive world.

Brenna: Yeah, but it’s not worlding in the way we worked in Oregon Painting Society, where we would make up a story and characters. That kind of worlding hasn’t been part of our practice with MSHR.

Birch: Our work now is actually very non-narrative, like very explicitly devoid of narrative. But I feel like people often see narrative in our work, even though we didn’t put it there. I’m interested in the idea of making work that sort of probes the part of the human mind that perceives narrative, and letting people fill that area in for themselves.

Brenna: I think maybe our work is narrative in the same way that our sculptures are realistic. They’re both pointing at reality through total abstraction.

Cool. OK, the very last thing that I wanted to make sure to talk about, that’s totally unrelated, is that you guys are the most indefatigable touring act I’ve ever met. You’re just like, kind of gnarly road dogs. What are your feelings on touring, and how it relates to all of this tradition and lineage that we’ve been talking about?

Birch: Well, touring was the first thing that we ever did, oddly enough, as MSHR. My old band ended at the same time Oregon Painting Society ended, when our worlds kind of disintegrated. And so then we took over on that tour as MSHR, and that was the first thing we ever did: this European tour, and then at the end of the tour, an installation. Since then, it’s just been part of the DNA for how we operate.

Brenna: And it’s just been the structure of everything, I guess. Because it provides this scaffolding for our work on a very practical level, and also just these incredible interpersonal human connections. It just kind of builds on itself, and now it’s just, like, how we move.

Birch: Where we’re from, in the corner of the United States, it’s a little isolated. Maybe if we were from a more international hub, we wouldn’t have grown up with the idea that we have to tour. But our work happens in person, you know, obviously; like, performances and installations are in-person things.

Brenna: We couldn’t just keep torturing the same fifty people in Portland forever. But so now we have this kind of geographically expanded community and it’s like we have to keep making the rounds to keep up the conversation with everyone.

:o)

.-. .-.

.--.-'_ .-.(_) )-.

( (_)' ( / __)

`-. / ) / `.

_ ) ( / /' )

(_.--' `._.' (_/ `----'

.-..-._ .-._..-.

.--.-' ..' (_)`-' (_) )-.

( (_) | / \

`-. | _ / )

_ ) `. ) .-/ `--'

(_.--' `--' (_/ `-._)

.----. .-. .-

/ `(_) )-. .---;`-'

/ / __) ( (_)

/ / `. )--

/ /' )( /

.---------'(_/ `----' `\___.'