FICTION // my lacuna

“whatever wall of myth, meant to separate dream from incarnate truth, to section it off from flesh, was gone”

Morning, folks--

Recent travels have had the unfortunate effect of reactivating my brain’s long-dormant “touring center,” the region responsible for making a person want to front a downpayment of gas money, start taking their meals at a Love’s or a Flying J, and spend weeks at a time performing sets of dubiously rewarding experimental tunes for handfuls of attendees in semiofficial concert venues across the country. It’s a lifestyle I hadn’t checked in with for close to a decade and, as with anything else fun that you had good reasons to eventually leave off doing, episodes of recurrence can be misleading; you tend to notice all the good stuff, overlook or forget the bad and the weird, and ask dumb sentimental questions like “Why did I ever stop doing this?”

So, in an effort to restore some cold truth to an otherwise all-too-cozy nostalgic exercise, I figure it’s worth reminding myself of some of musical touring’s more questionable aspects: its profound arduousness, its function as a machine for self-doubt and disappointment, and the generalized havoc it wreaks on a traveler’s circadian, metabolic, and straight-up mental capacities.

To that end, I’m resurrecting the following chunk from an old manuscript of mine, Ill Tomb Era (which I’ve excerpted before, and will excerpt again). In the section below, a member of a touring sludge metal group named for an Austin Osman Spare sex magic ritual reflects on the success of his band on the DIY circuit, even as he acknowledges the troubling effects it--and the band’s contemporaneously developing occult practice--had on his sense of reality. A mild exaggeration of the IRL touring experience, if that.

This piece was released in a long-ago short run zine, but has also had a bit of a tail in that some of the magical language it contains also found its way into my short story “Ladies of the Privy Chamber,” which X-R-A-Y published last year. Also, “MY LACUNA,” the name of the fake TV show in the text, became the name of a real song on a real album by my (mostly-)real band. For all its latter day echoes, though, the text has some solid moments in its original form, which is to say that I’m not entirely embarrassed to be reposting it below. I am pretty sure, for one thing, that it’s the only novel excerpt ever written to include both the terms “trompe l’oeil” and “oogle bicker sesh” within the space of a few paragraphs.

Enjoy, if that’s an option for you.

Love,

Mark

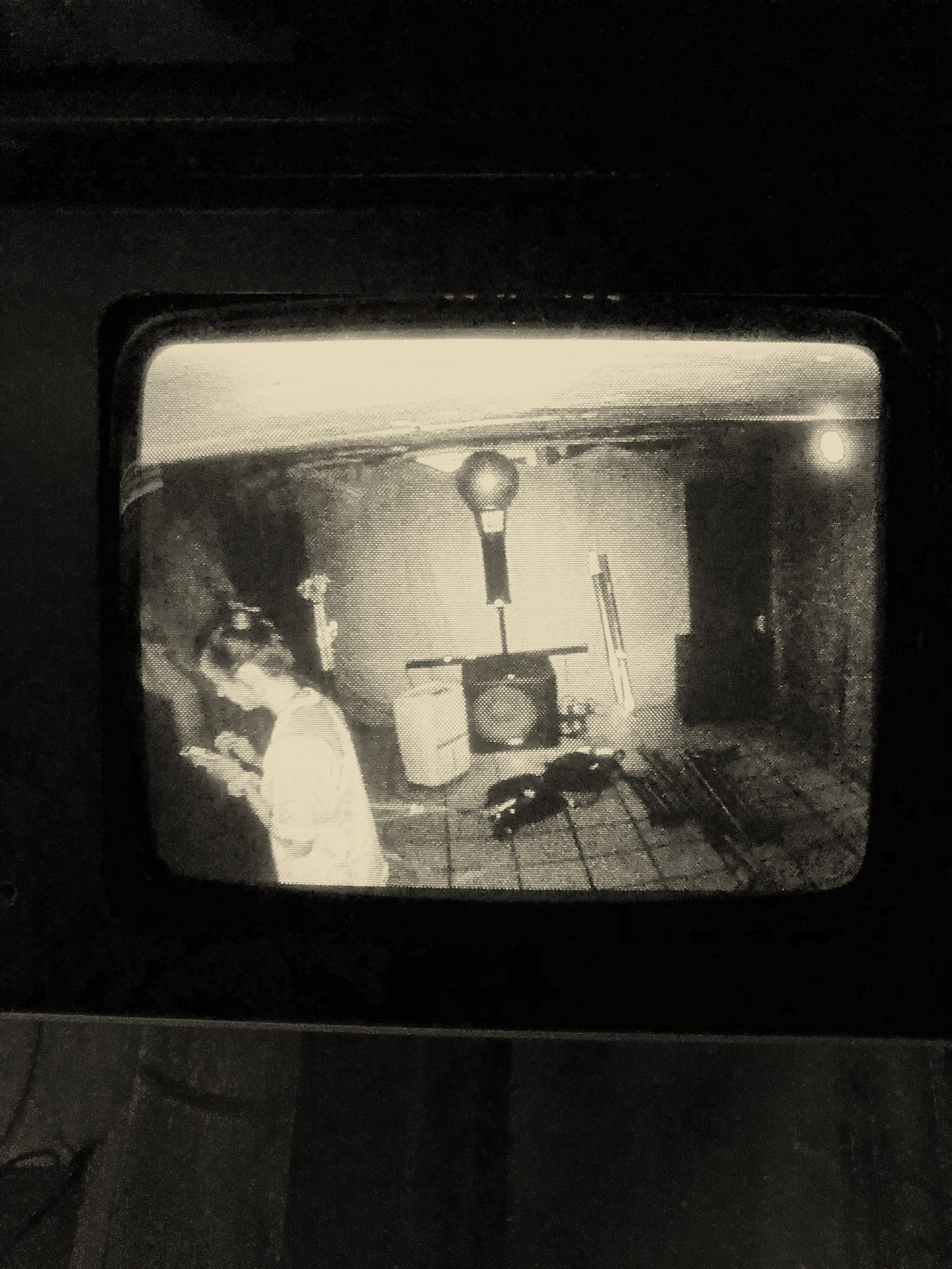

We now rise for the TV/VHS combo unit.

By strict tick of the clock, the Earthenware set tonight lasts forty-four minutes, comprising two, maybe three long-form song sections, depending really on whether you count that drum intro as a separate track or just a warm-up. Sometimes an audience member, nervously approaching in the post-show glow, will ask about structure—how the band members plan their performances, what quantity is predetermined and what’s improvised, how each knows when to stop, or to start, or to change. Do they practice? Hank doesn’t ever answer, and nowadays if Angus does, it’s only elliptically. It’s become clear, in lieu of any useless explanation, how much easier it is to couch one’s intentions in weedian euphemism: “No plan,” or “We stop when it’s over,” or “It’s all one thing,” that kind of line. It comes off as so much rocker bullshitting, obviously, though kids at shows seem to get into the apparent vagueness of such pronouncements, always nodding enthusiastically, taking corroborative sips of their beer, asking if they have tapes or records for sale. But tonight is different. No one, in the moments following Hank’s final cymbal crash, makes a move for the ad-hoc stage area, or the merch table, or the upstairs. No one claps. Tonight the kids are stock still. Not necessarily a big deal; every audience has members who are more sensitive, more fantasy-prone, more apt to apply a directed sense of expectation to the proceedings. Chances are they’ve seen the band before, noted their effect, done some research, come prepared. There are little adepts springing up all along Earthenware Virgin and Child tour routes.

“You might imagine it as a doorway.” Angus’s earliest bit of instruction, freshly wrought symbol on a scrap of repurposed paper in front of him. A loose oval, an egg shape, painted in darkened purple. To be pondered, fixed on with concentration, stared at wordlessly, revivified in the incorruptible space of one’s steadfast attention before being carefully transposed in its tiniest aspect, its subtlest metaphoric iteration, onto a field of whiteness, unified with its complementary color component and enlarged, slowly, to greater and greater statures: to the size of a key; to the size of a knob; to the size of a door. “Carefully look over the door in your imagination,” his hands up, fingers outstretched, unwitting, unplanned. It was sunrise. “Now open the door.” And he stepped through into color: shapeless cloud of blue, long hooks of deep orange, swirling wormlike protrusions, maybe even a clean silver outline—scallop-edged, cylindrical and acutely reflective—that resolved vaguely into a shape of real-world correspondence, a form, a material, a vestment, an evening dress and maybe even, yes, its wearer: tall, gaunt, hazy features marked by black, by thickly caked, garish black makeup. The glowing pandrogyne. Their first invocation.

“Black,” that same first day of instruction, Hank drilling him on the operative symbols, her back turned in the dim space of her country bedroom. “World’s night rolling onto world’s night, a goddess in destructive aspect, swallowing colors as she swallows forms but always luminous when she can be definitely observed, always gleaming.” She was on the other side of the window, silhouetted just beyond the illuminated space of the slat-lit air, faded, faraway, but defined: what he saw was her shape, her rigidity, wrestled down to a point of absolute control; her fixed, tight posture, steadfast tone of voice. Spirit coiled like a whip, like a rattlesnake. Her power.

“Picture it.” Angus had had to superimpose the symbols, steady, using the same infinite care with which he conceived the doorway. “Do you see it?” In his clearest, most irreducible imaginative state, the dark shapes were blotted by the contours of the black layers onto which they were applied. Hank began to turn to face him, slow, tightly clipped, the gleam off the windowglass spilling onto her side: lighting right shoulder, then right hip, creeping along the pale curve of her and moving slowly, very slowly, inward. “No dark space,” emerging, all resplendence, all flowing, “no conditions of light in the physical world,” gliding, radiant, closer, “can obscure black.”

Her manner was intense, methodic. Cruel, sometimes. So was the magic she was teaching him; cruel, or at least indifferent, uninterested in showing itself, all but imperceptible when effected as rote ritual or hollow diversion, apt to up and vanish on you if you ever found yourself thinking of it as an aimable, directed tool, a means of achieving something. In the way he sometimes caught himself thinking of her—a detail, her hands, a yellow strand of hair, the restrained ball-turn of her shoulder through the skin—as something knowable, something he could really see all of; he’d try, and instead just lose her entirely. Their work was the same. It was a mode of conception, a language for naming, for beginning to name, what was there, what had been waiting there, in untroubled latency. It was exhilarating, freeing; and if it was painful, it was only the pain of having pretended, of having coasted on wrongheaded assumptions, of having been without her and her guiding touch for so long.

The new thinking wormed its way into everything, to the point that he began to have trouble—or maybe just sort of stopped bothering—distinguishing waking reality from dream. A conditional space had opened, and every lived moment now passed through it, existing in tantalizing suspension before sliding, down, into one pat realm or another. Still, nothing really landed, not if landing denoted consequence, permanence. All his inherited definitions were shot for good: a verifiable, sensed experience would turn out to be nothing more than an idle thought. A wholly mental exercise would manifest physical effects. Memories would come back to him, their origin and provenance a complete mystery; had it happened to him or to someone else? Was it past or future? Had he lived it or had he dreamt it?

Angus began regarding everything and everyone as a possible figment—or, not a figment, actually, more like a function—of his subconscious, applicable to the strictures of waking life on a sliding scale. Nothing too dramatic; he understood that just as the old, blandly physical world operated according to laws, so did this new one, and so he didn’t feel any great urge to, say, jump off a building and try to fly. But strangers, friends, roommates—when Hank started teaching him, he was living at a crummy squat in town—people claiming to know or be related to him: all came to Angus from within this thickly folded conditional space out of which they could cut either way, and every perceptible moment brought with it this announcement, this gentlest even-toned murmur that said “Not so fast,” that warned against its own believability, that said it was all part of a larger, less fixable order. Soon all talk of dreams and wakefulness, of hallucination and reality, was moot, academic. It was all one thing.

No doubt it was what made their band so good. The music—and the recordings, performances, and traveling that were its expression—began quickly to take on this same widening of definability, this same unyielding charge. The conjuring ground became the studio, the stage. Touring, already an exercise in schizoid cognition—wherein you wake up in unfamiliar rooms full of unfamiliar people from unfamiliar towns who all seem to know you—actually hereabouts turned into something resembling a movie, or a sitcom, or a cartoon flipbook: a continuing series of discrete adventures in which Angus, though technically a participant, was much more a passive observer, watching Hank and himself from the sideline vantage of a fly-on-the-wall, third person tip.

He remembers—or, heh, dreamed, or anyway, seems to have observed—one such sitcom scene, another anonymous morning at another anonymous punkhouse though, for all the archetypal feel, loads of specifics still beckoned: some den or TV room, stacked trays of dirty dishes, empty bottles and half-drunk tallboys, what frat dudes call “fallen soldiers,” piled up at odd angles and more often than not cantilevering vertiginously over the edge of this shabby old coffee table, little snatches of defacement, nicknames, insults, ________ WAS HEREs, crude dick-and-balls drawings keyed into the woodgrain over the years, all this in addition to the band stickers, desiccated lumps of old gum, show fliers, guitar picks—generic component pieces of a whole punker’s trompe l’oeil display, really, all stacked up one on top of the other, layered geologic strata that still managed to offer everything for direct perusal on an individual basis, nothing hidden or covered up. Kind of a sinister edge to the arrangement, or this was Angus’s take, anyway, when he seemed to come to—facing the TV on a low plaid cushion-shorn couch, cocooned in a sleeping bag, curled up, actually sort of half-bent, hard-angled in awkward orthogonality. No particular urge to understand where in physical space he was, he opted to just take a look at the TV set, in whose gleaming lens he caught a glimpse of his own reflection: matted, greasy hair; bleary stoned eyes; an inverse couchprint mapped across his cheek. The idea, if he had to guess, being that he’d been dozing in front of the TV for a while now, and should probably get back to it.

Which he was all set to do, except just then in came these faraway giggles, sounds of excited conversation from outside, first faint, then louder. It was coming from a couple of unknown oogles, ripped up bleached gear on, combat boots kicking open the bottom part of the half-torn screendoor, beaded rat-tails clanging against a cupboard, open-shut woodclop of a pantry grip, vacuum snap of a crinkly chip bag being opened. The whole symphonic bit. Maybe this was their house, maybe they were just hanging, but either way they were in a cozy enough mood to flip on the TV, step hastily over Angus’s sleeping form and take seats on the couch’s unvarnished wooden armrests, chewing with open mouths and shushing each other.

“It’s been on for like,” Oogle 1 whispering though still appreciably loud, “we missed like half of it already.”

“Shh who cares?” Oogle 2 wiping some nacho cheese on Angus’s green nylon sleeping bag shell.

“What is this commercial?” On the TV, a man and a small child could be seen in hunting regalia, holding up rifles and tracking a baby deer in their sights.

“It’s hunting—it’s for a hunting equipment thing, a store or something.” Angus was kind of half-slitting it, eyeing the screen but keeping things squinty enough that he could pretend to be asleep should that prove a better policy. In the commercial, the child took a shot, and the deer dropped.

“This kid is sick. He’s an amazing hunter.” The man high-fived the child, and the image froze before slowly fading out.

“I wonder if we should clean up? It’s nasty in here, show was like three days ago,” which answered one of Angus’s dissociative ponderances, namely What relation does this house bear to my band, or to my tour, or to me? He went ahead and let his eyes enjoy their full dynamic range and saw that the main program was returning from the ad break.

“Shh, shh, it’s on.”

“Turn it up a little.”

“There’s no—I can’t find the remote. Shh.”

On the screen, a red curtain appeared and a lush orchestral theme came swelling in the background as the program’s title, rendered in gaudy, old-fashioned silvery calligraphic type, slowly slid into focus atop the velvet: “MY LACUNA”. The title card faded, and an announcer in a tuxedo—flickering a bit, seeming to blend and unblend with the background from frame to frame—stepped onto a bare stage, lifted an old RCA ribbon mic, oriented himself toward the camera, and made with a big smile.

“Welcome back. In our next story, a teacher presents her students with a very typical lesson—but gets some very atypical results!”

A dreamy harp glissando marked the scene transition, and the setting shifted to a classically-appointed approximation of a gradeschool classroom—map of the world, cursive letter chart, shiny chemistry set.

“What is this?” Angus whispered. “What show is this?”

The oogles ignored him. On the screen, a teacher in a plain smock dress and a high bouffant was handing out worksheets to a group of kids, probably eight or nine years old, clean-cut at orderly rows of desks, all with the same sort of geewhiz, Mayberried-out look to them.

“But Mrs. Cyclamen,” as a hand shot up from one of the students, a buzzcut, pug-faced little dude with buckteeth, “you forgot to give Sandy her dictation sheet.”

It was true; as the camera panned up to the little girl playing Sandy—meek, skinny in overalls and this shock of, yeah, blonde hair—it stopped to linger on her empty desk.

“Is that—Hank?” if the oogles heard him, they didn’t show it, but, having found the remote (it’d been inches from Angus’s sleeping-bagged foot, tucked into an interior couch edge), one of them did turn up the volume a bit.

“You’re right, Bobby,” Mrs. Cyclamen with an obliging smile, “except I didn’t forget anything. Since Sandy scored the highest on last week’s spelling test, she isn’t going to be doing the dictation at all. Instead, she’s going to be giving it!”

Every kid suddenly turned to look at this Sandy, who just sort of stared down, fidgeting with a pencil, giving a slow shake of her pigtails. The others, oohing at the refusal, pivoted back to Mrs. Cyclamen.

“Now, Sandy,” a firmer edge to the teacherly tone, “if you’d rather explain to the principal why you didn’t listen to your instructor, that can certainly be arranged too!”

The oogles chuckled a bit as, onscreen, a previously-unheard studio audience erupted in hysterics. After pausing for the laugh, Sandy swallowed, stood up and held a hesitant hand out for the teacher’s master sheet. Mrs. Cyclamen handed it over, flashed a pencils up gesture at the other students, and took a seat at the vacated desk.

“Damn,” Oogle 2 whispered, “I wonder what’s gonna happen.”

“Shh. Just watch.”

A subtle sort of high buzz had kicked up on the soundtrack. “Do you guys—” though Angus knew by now that he’d be getting no response. “Do you hear that?”

“‘There’...” as Sandy, shaky-voiced and tentative, she started to read from the sheet, “‘are’...” and the camera panned over the other kids, scratching away with their pencils over this growing buzzing, “‘many’...” over to Mrs. Cyclamen’s approving smirk, “‘gods.’ Colon.”

“Whoa,” slackjawed from Oogle 1.

“‘There are many gods.’ Colon. ‘The ones’...” scritch-scratch drowning out as the higher-pitched sound kept rising, “‘you meet’... ‘above’... comma,” as Sandy took a longer pause here than normal, looking over at the teacher and getting a little ‘go on’ nod, “‘and the ones... you meet... below’—look,” turning to face the camera with a sudden terror, “this is, this isn’t a show, this is real—” and the high buzz overtook her voice before the film seemed to burn, the image cut to white and the sound dropped out, leaving a low ringing aftereffect and a blank screen.

“I don’t—is this part of it?” The oogles just sat in silent expectation, ignoring Angus.

Just as suddenly, the picture returned. The scene was the same, except there was a new actress playing Sandy: same clothes, same hair, but the hesitant look was gone, replaced with a knowing, coyly performative little girl grin.

“Did you all get that?” Mrs. Cyclamen wanted to know of her students. “Any questions? Sandy?”

“Just one,” as new Sandy fixed on the camera, did a little hair flip and held for the punchline: “Next time, can someone else score highest on the spelling test?”

The characters, the studio audience and the two oogles began roaring with laughter, and the soundtrack was overwhelmed with applause.

“Called it,” Oogle 2 between sips of an old beer.

“No you—when?”

“Before, when we were talking about it, well I didn’t—I mean I didn’t call it out loud but I knew they were gonna do a twist.”

Onscreen, the actors stood up to take their bows and blew kisses into the crowd as the curtain fell. “Yeah right; you had no idea what was gonna happen.”

“I know, that’s how come I knew it would be a twist. I knew that they’d do a twist; I called that.” The applause continued as the announcer stepped back out in front and gave a couple of bows.

“You didn’t call, or know anything. You thought something, maybe, if that.” The announcer pointed out to the audience and clasped his hands in mock thanks, bowing again. Flowers were being thrown up from the audience and snatched off the floor by quick-moving stagehands.

“My actions showed that I knew,” this oogle bicker sesh still going as the camera swiveled out to the audience, whose members were up on their feet giving a standing ovation. As the shot panned across the studio, of course Angus saw it: a vision of himself, harshly lit in a suit and tie, sweaty off of the hot gel lights, smiling broad across the lurching broadcast framerate, applauding effusively.

And as he woke—or next came to, or clicked back into awareness—it was without a signaling jolt, without any particular demarcation of renewed safety, just a slow superposing of another layer of being, fitted loosely overtop the old one, and, well, seemed it had been her making that high-pitched sound, his girl Hank, back at home, the two of them, no grimy punkhouse at all but here, in bed, with her vibrating next to him; a high nervy whine, louder and softer, coursing oscillation peaked against the scratching of the pencils in the classroom, the timid-voice of the actress reading the dictation but with this breathy, voluptuous component that hadn’t transferred into the scene, this heaving sigh and Hank pulling on the bedsheets, running hands over herself in blind somnolence, sliding legs, rubbing arch and nape against his adjoining form.

“Where’d you go?” in a whisper. She almost never asked him.

“I’m not sure. We were on tour.”

“I was there?”

He nodded into the hollow of her shoulder, ear pressed to the low moan of her breathing. “I think. You were a little girl.”

She craned to face him and the sound sharpened—a diaphragmatic, gut sound, her muscles verifiably tensing along his side as she moved, skin alive with impossible heat—a forceful shaping there in the dark, that charge being borne willful across all unbridgeable space through to the den, to the TV, to the classroom, to the voice, to the faces he knew were still watching them. Whatever wall of myth, meant to separate dream from incarnate truth, to section it off from flesh, to attenuate the soft curve of joy against strength, against force of imagination, was gone, and her eyes, when he chanced to look, had gone abyssal, pointedly white, staring out to void.

Later she told him his had too. Soon he was looking up during their sets into the faces of kids in the crowd and noting that their eyes were doing the same thing. Or looking down at his hands on the guitar to find them playing perfect licks he’d never learned. Or gazing out into the space of the venue, into humid conditional space, and seeing shapes, colors, forms all obligingly, effortlessly surrounding. The stage, the basement, their summoning ground. The Earthenware Virgin and Child, their gleaming evocations and their amp-warped, time-freed adherents.

.s5SSSs. .s s. .s5SSSs.

SS. SS. SS.

sS `:; sS S%S sS S%S

`:;;;;. SS S%S SS .sSSS

;;. SS S%S SS S%S

`:; SS `:; SS `:;

.,; ;,. SS ;,. SS ;,.

`:;;;;;:' `:;;;;;:' `:;;;;;:'

.s5SSSs. .s5SSSs. .s5SSSs.

SS. SS. SS.

sS `:; sS `:; sS S%S

`:;;;;. SS SS .sS;:'

;;. SS SS ;,

`:; SS SS `:;

.,; ;,. SS ;,. SS ;,.

`:;;;;;:' `:;;;;;:' `: ;:'

s. .s5SSSs. .s5SSSs.

SS. SS. SS.

S%S sS S%S sS `:;

S%S SS .sSSS SSSs.

S%S SS S%S SS

`:; SS `:; SS

;,. SS ;,. SS ;,.

;:' `:;;;;;:' `:;;;;;:'